2024

Solo Exhibition: The Patient Cries, Lunds Konsthall, Lund

2019

Solo Exhibition: Day Craving Night, Spike Island, Bristol

A Glossary of Distance and Desire

2018

The Orchard of Resistance

2017

Finding the Edge

2016

Promotion Europe

2015

Have you ever seen a fig tree blossom?

Souvenirs for the Landlocked

2014

Solo Exhibition: Becoming European, Moderna Museet, Stockholm

Disclaimers

A World of Blind Chance

Men in Buckram

2013

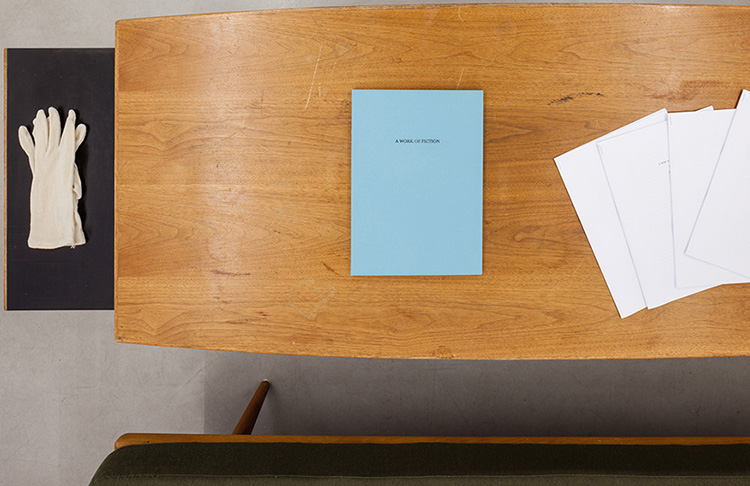

A Work of Fiction

A Work of Fiction (Manuscript)

Metatext

Eternity and Infinity

On Writing

The Weight of IASPIS

Line No.3 (Holy Bible, Selkirk and Crusoe)

A Hook or a Tail

2012

successes, failures and in-betweens

Billboards

The Library of Unborrowed Books

Line No.2 (Holy Bible)

Location: Date: Time:

Which no one will ever see

Time will not record everything

Becoming European

2011

Ö (The Mutual Letter)

The Risk of Being in Public

2010

He is really only a white stain

Line No.1 (Holy Bible)

2009

Untitled (Tree Top Project)

Our Home Weighs 1.223.990 grams

Destination:

The Concise Book of Visa Application Forms

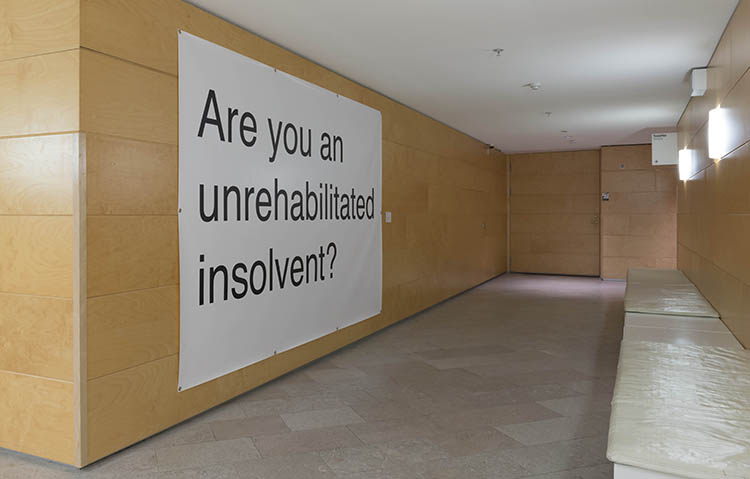

Solo Exhibition: The Patient Cries at Lunds Konsthall, Lund, 2024

Photos: Olof Nimar. Text by Debora Voges, curator, Lunds Konsthall.

Supported by SAHA, Turkey. With thanks to Johan Hjerpe.

Artist and writer Meriç Algün explores the world around her and her own inner world through her writing, and shows her discoveries in a new solo exhibition, The Patient Cries, at Lunds konsthall. The exhibition centres around one of Algün’s literary works, which addresses the role of the stepmother, mental health, and caring for others. Visitors will take on different roles in the exhibition’s installation, which consists of a full-scale replica of the artist’s own home. In this time, when political and social discourse is increasingly focusing on the issues of women’s reproductive rights and fertility, Meriç Algün’s deeply personal works are particularly relevant and incisive. Alongside the exhibition, a series of talks and readings will be organised in collaboration with Lund’s Public Library.

Solo Exhibition: Day Craving Night at Spike Island, Bristol, 2019

Photos: Max McClure. Text by Carmen Julia, curator, Spike Island.

Supported by SAHA, Turkey. With thanks to Goldin+Senneby.

"For her exhibition at Spike Island, Meriç Algün presents a series of new and recent works that explore the precarious nature of love and the environment in a world that is obsessed with individualism, borders and consumption. In the face of global warming and the extinction of life forms, alongside the rise of all kinds of constructed negativeisms such as racism, terrorism, separatism or consumerism, Algün’s exhibition evokes the idea of togetherness under threat. Gathering a wide range of sources from the Carboniferous period to today, Day Craving Night takes the form of a spatial collage and draws analogies between love, nature and culture.

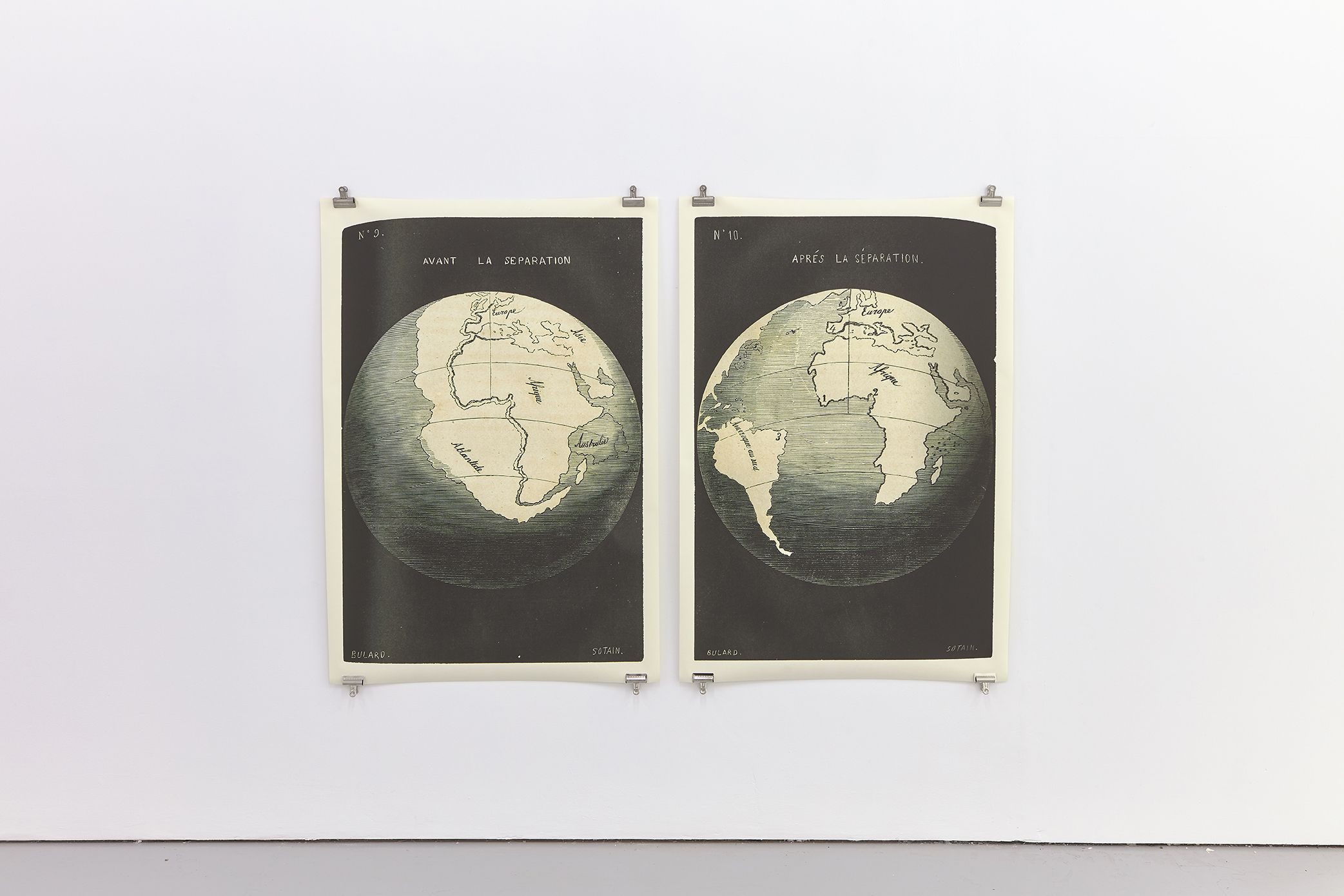

Upon entering the gallery, a reproduction of a print by the nineteenth century French geographer Antonio Sinder-Pellegrini depicts the world before and after the separation of the continents1, and serves as an introduction to one of Algün’s ongoing concerns: the rise of borders and their impact on the formulation of human desire. The idea of a large-scale displacement of continents has a long history. In 1912, the first comprehensive theory of continental drift was proposed by the German meteorologist Alfred Wegener. Continental drift is the movement of the Earth’s continents relative to each other, thus appearing to “drift” across the ocean bed. Bringing together a large mass of geological and paleontological data, Wegener concluded that throughout most of geologic time there was only one continent, which he called Pangea. Late in the Triassic Period, Pangea fragmented, and the parts began to move away from one another. The idea of continental drift has since been superseded by the theory of plate tectonics, which explains how the continents move.

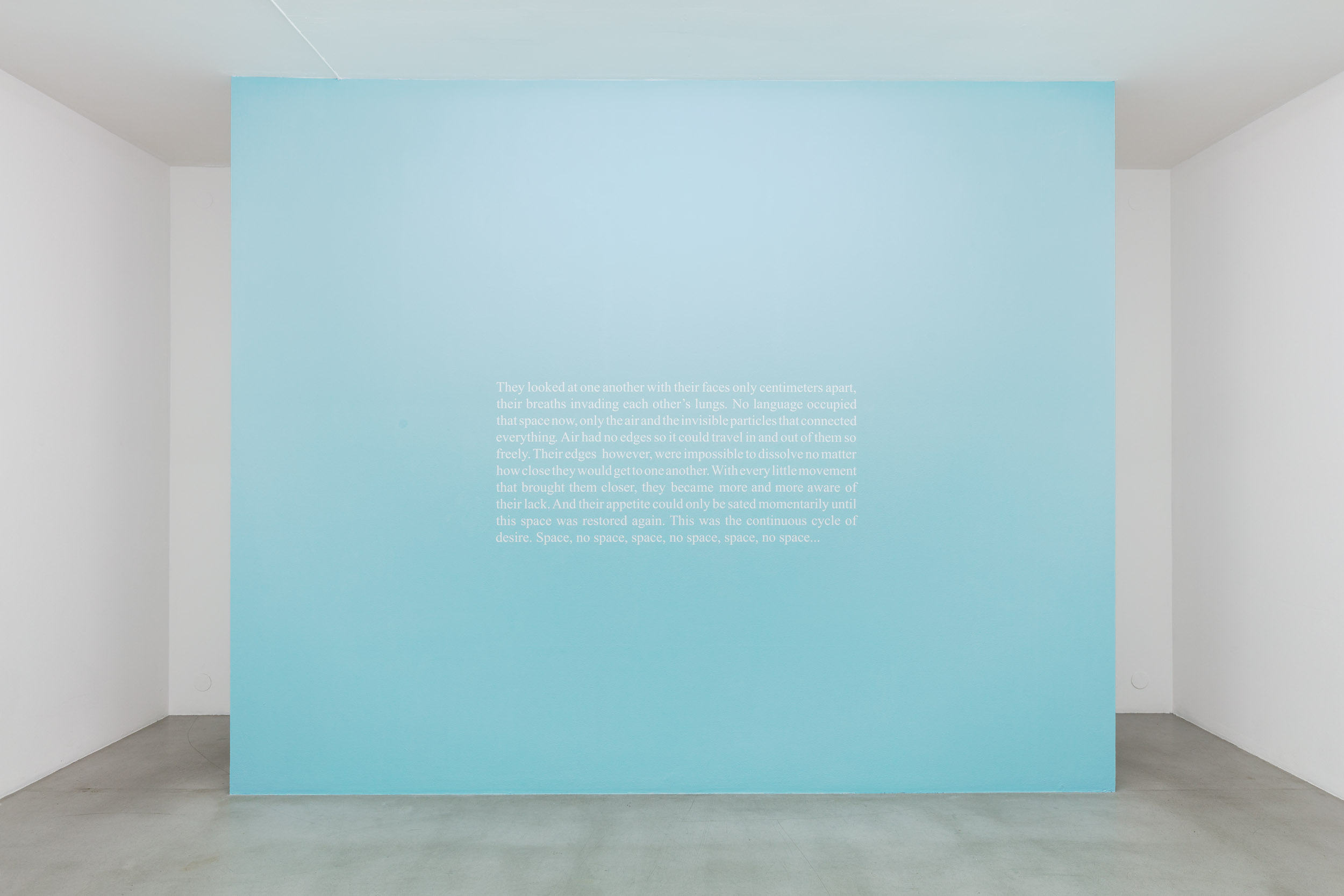

Plate tectonics and continental drift theory is further explored in gallery one, where the work Finding the Edge (2017) stands as an allegory of Pangea. The work consists of a freestanding shelving unit cut into seven sections which correspond proportionally with the surface area of each of the seven continents. Similarly, the gaps between the rows of shelves relate to the surface area of the oceans. The shelves display a variety of objects relating to Algün’s research on continental drift and Eros (the Greek god of love), ranging from ferns and animal fossils, to world globes, handmade books, videos and sculptures, drawing parallels between the separation of the continents and the origins of human desire; borders awake our desire to transgress them, to go beyond and across.

Finding the Edge takes its title from a chapter of the book Eros the Bittersweet (1986) by Canadian author Anne Carson, where she speaks of desire and love in relation to the edges and boundaries of the self: ‘Eros is an issue of boundaries’, she writes, ‘He exists because certain boundaries do. In the interval between reach and grasp, between glance and counterglance, between ‘I love you’ and ‘I love you too’, the absent presence of desire comes alive.’2 Eros symbolises want, lack and desire for that which is missing. As such, according to Carson, the experience of love or desire as lack alerts a person to the boundaries of herself, of other people and of things in general.

Alongside Finding the Edge, the text work Edges (2017) reproduces an abstract from Algün’s ongoing novel, an attempt to capture the intimacy between two lovers; in the proximity of their bodies, borders and boundaries grow taller, while distance grows longer. Opposite, a 4.5 metre-high wall drawing depicts the legendary ghost ship the Flying Dutchman, doomed to sail the oceans forever. For years, an image of the Flying Dutchman featured in the logo of the Dutch airplane company KLM. In the context of the exhibition, the ship’s eternal journey stands for the never-ending search for the object of desire; a search that has come to represent our susceptibility to late capitalist modes of consumption, which exploit our innate tendency to want what we don’t have, exposing the relentless drive of consumer culture to create new wants and needs.

A collection of full page magazine adverts of Calvin Klein’s iconic fragrance Eternity, dating from the late 1980s to today, hangs on the gallery’s perimeter walls. If desire is our driving force, then appealing to emotions is the most powerful way to persuade consumers to act. As such, the fragrance has variously been described as ‘An unchanged constant, a new forever... a visual history, [with] its timeless values of love and commitment’, and for a period of nearly thirty years, the adverts have featured the same model, Christie Turlington, who is portrayed with different men and children, perpetually roaming in eternity in search of the object of her desire. In her last advert from 2017, she is portrayed side by side with her actual husband on a beach in a British overseas territory, her voice repeats: ‘I was searching and then, I have found you and I will love you for ever and ever.’ Husband, beach and fragrance fuse in everlasting desire.

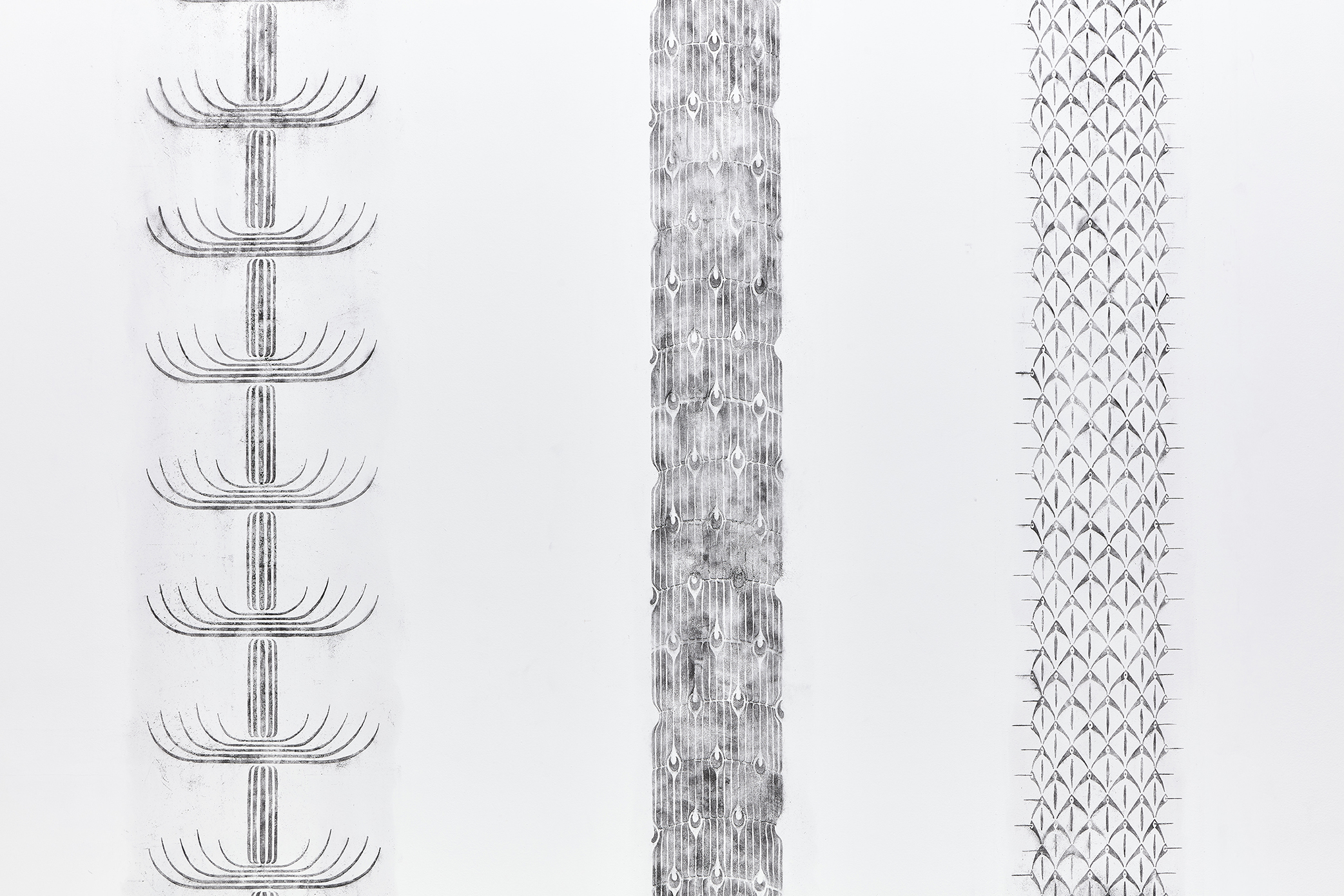

Elsewhere in the outer perimeter, a ghostly coal forest pattern wraps around the gallery walls. The Plot (Utopia Bloemen) (2017), a collaboration by the Swedish artist duo Goldin+Senneby with designer Johan Hjerpe, is a multi- layered work that connects capital, art and pre-human history. The work comprises a plot of land that the artists acquired in Genk (the old coal mining area of Belgium), a poem by Turkish-born Belgian poet Mustafa Kör about his father’s uprooted life as an immigrant working in this region, and a series of stencils depicting patterns reminiscent of carboniferous-era fossils unearthed in this same location, which Algün has borrowed for her exhibition. Those plants which originally decayed into coal have come to new life here in the form of a coal-made mural. A number of fossils from that same period are displayed alongside a series of clay works which are an imprint taken from the inner palms of two holding hands.

Finally, a section of a tree trunk with two equal-sized growth rings hangs on the wall. Inosculation is a natural phenomenon in which the trunks, branches or roots of two trees grow together. In forestry, such trees are known as gemels, from the Latin word meaning ‘a pair’.Here Algün makes reference to French philosopher Alain Badiou’s theory of love, when he writes ‘love is a Two scene’, a statement that offers a dual perspective and represents a basic political matrix. According to Badiou, in love two different individuals come to share a ‘scene’, a situation, a world, but in such a way that their radical difference is preserved, embraced and renewed. Love is no longer an experience of the other, but an experience of the world under the condition that there are Two; the world is no longer yours nor mine, but our world.3"

1 Antonio Sinder-Pellegrini, La création et ses mystères dévoilés; ouvrage où l'on expose clairement la nature de tous les étres, les éléments dont ils sont composés et leurs rapports avec le globe et les astres, la nature et la situation du feu du soleil, l'origine de l'Amérique, et de ses habitants primitifs, la formation forcée de nouvelles planètes, l'origine des langues et les causes de la variété des physionomies, le compte courant de l'homme avec la terre, etc. Avec dix gravures, 1859.

2 Carson, Anne. Eros the Bittersweet, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986.

3 Badiou, Alain with Truong, Nicolas. In Praise of Love, London: Serpent's Tail, 2012.

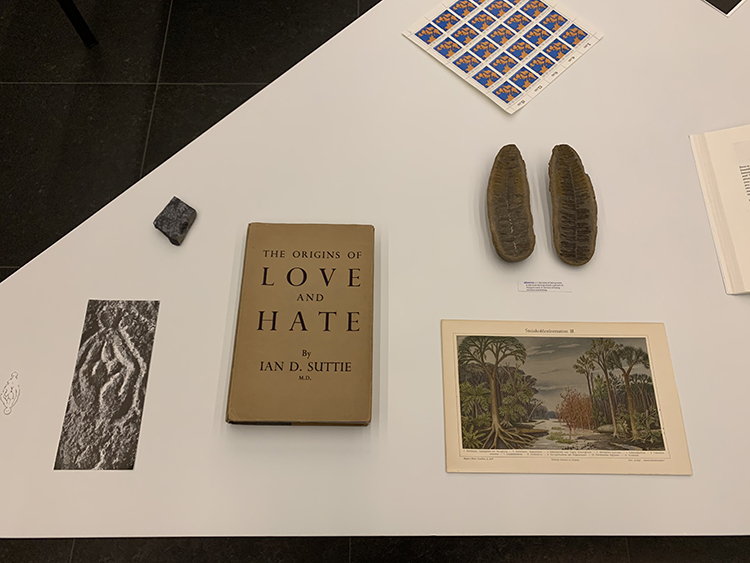

A Glossary of Distance and Desire

2019

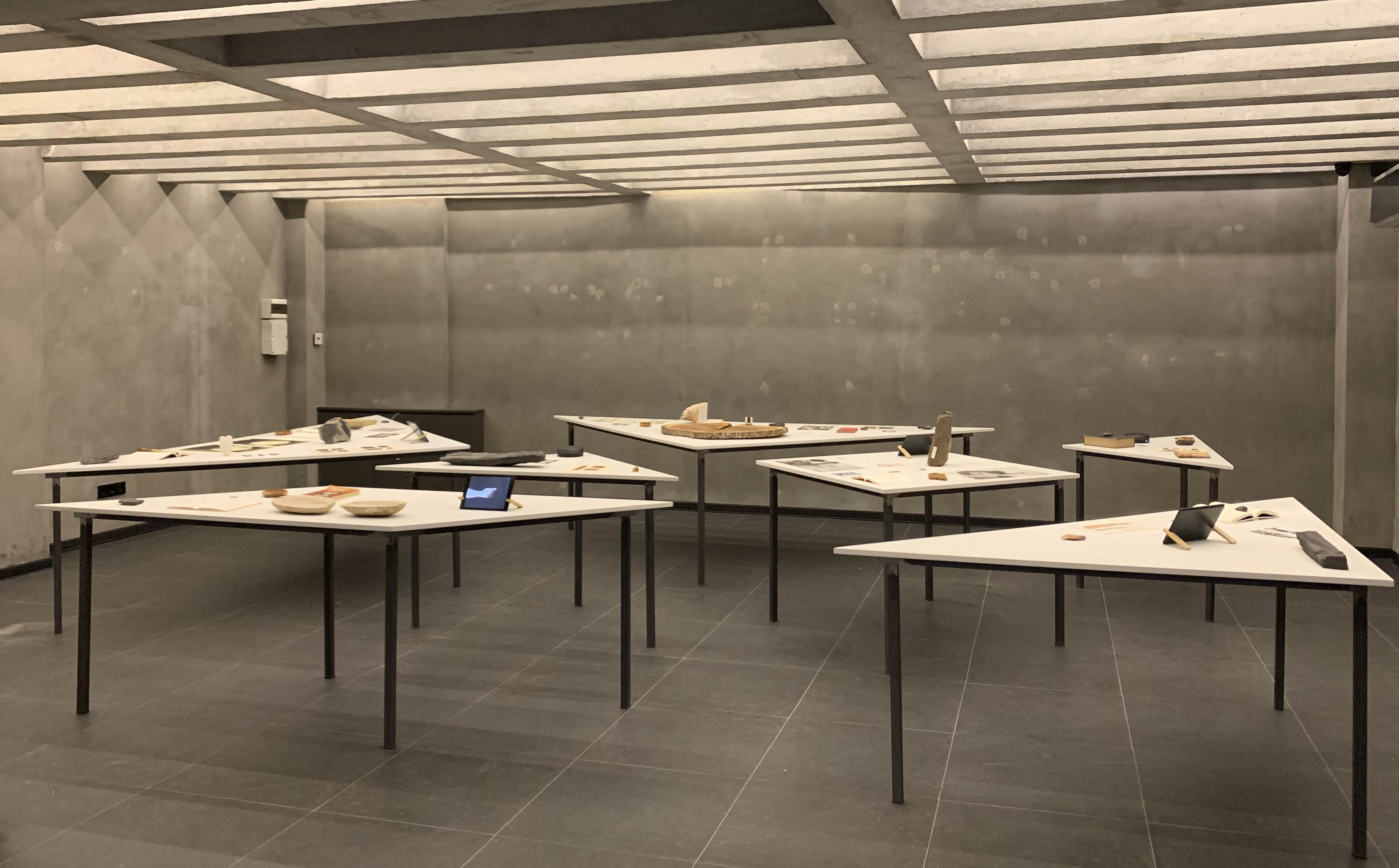

Installation with objects, videos and sound in seven various parts

300x300x80cm in total

Exhibition view: Riverrun, Istanbul

Thanks to Can Aytekin, Kıymet Daştan, David Larsson and Riverrun, Istanbul

A Glossary of Distance and Desire stems from an interest in the separation of continents, formation of boundaries, love and desire. The work takes the form of a tangram table –a dissection puzzle consisting of seven shapes that can be arranged in different configurations. Placed on the tables are different materials like plant fossils from the Carboniferous era, clay sculptures, maps, texts and a range of objects related to distance and desire. The objects are open to associations and interpretation, not unlike words waiting to be placed into a sentence. It draws our attention to how, in a world of fetishized individualism and reckless consumption of earth’s resources, love too is under threat and the only way out is through finding ways to relate to one another.

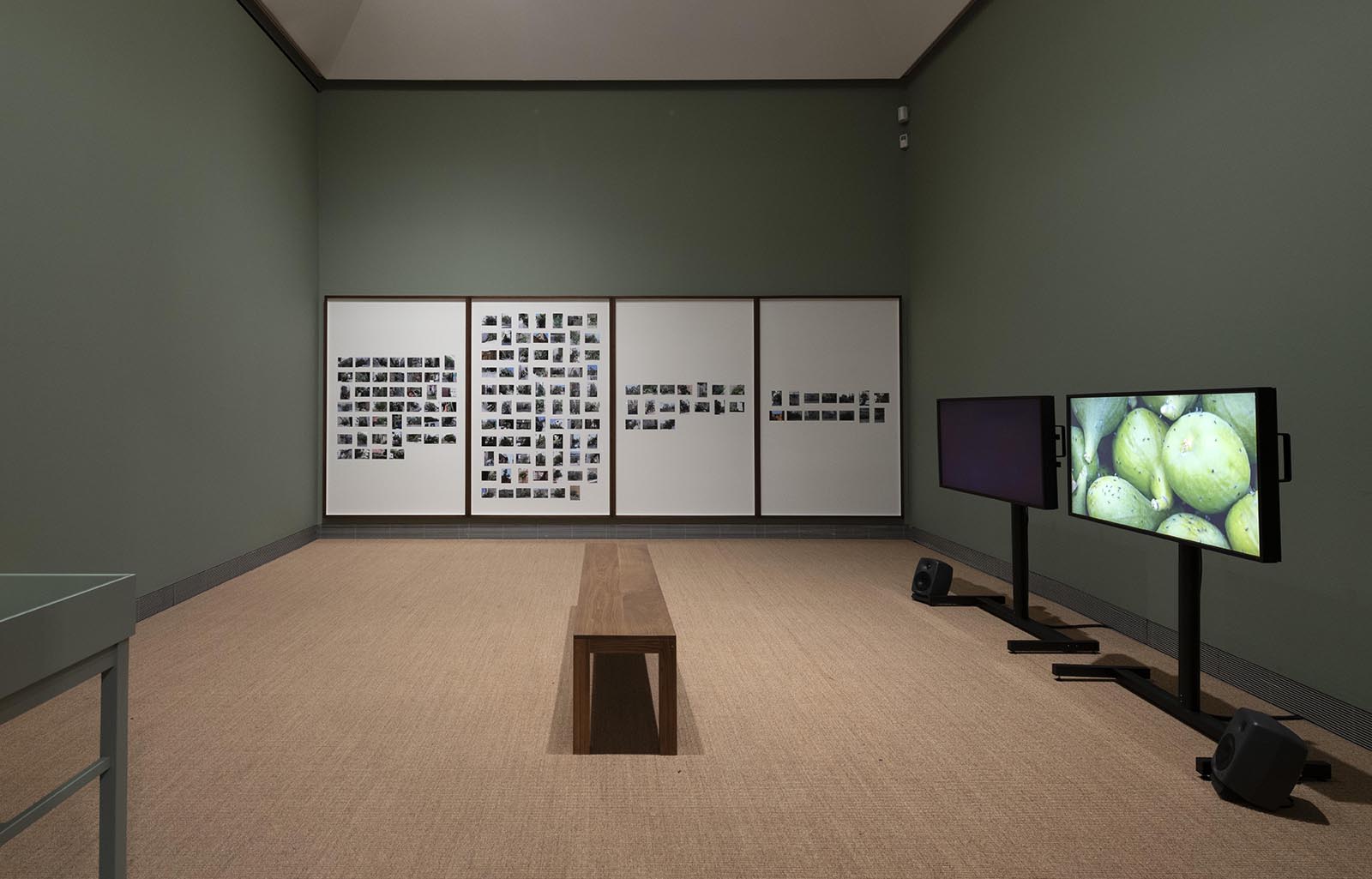

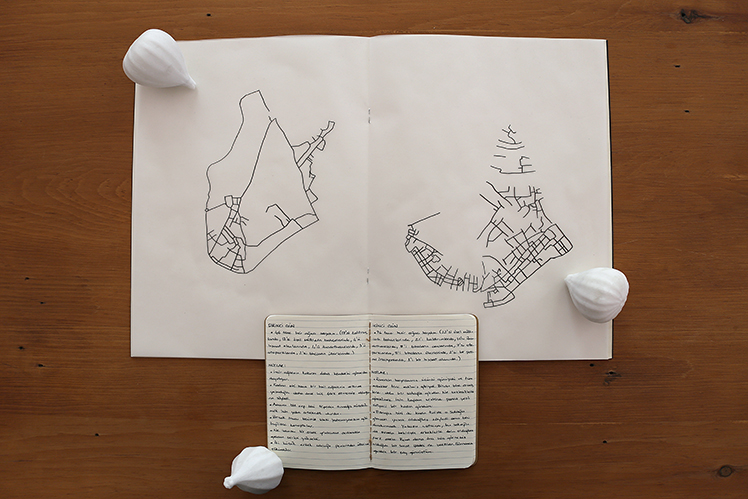

The Orchard of Resistance

2018

Mixed media installation with video, photography, notebooks, marble, wall paint, carpet

Video duration: 17 min, frames: 225x146cm each, glass display case: 126x66x90cm

Exhibition view: With the Future Behind Us, Moderna Utställningen, Moderna Museet, Stockholm

Photo: Åsa Lundén, Moderna Museet, Stockholm

Thanks to Nils Fridén, Velourfilm AB and Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

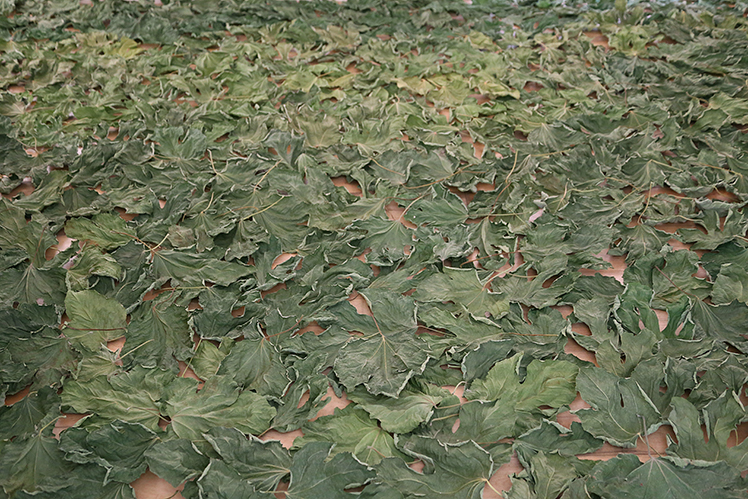

The central Galata neighbourhood in Istanbul was a rural fig tree orchard in 100 AD. During a stay there, Meriç Algün looked for the symbolic remnants of the lost plantation. As in many other works, she approached her subject in an investigative manner. She walked around methodically photographing the fig trees that today grow between the cobblestones, in courtyards and on parking lots in the area. Moving around in the area as a woman provoked a lot of reactions, particularly among men. She wrote down what she saw during her rambles in a notebook and reflected on the experience of being watched.

At the same time Meriç Algün conducted research on the common fig, which proved to have many connections to what she experienced on her walks. The fig is a “false fruit” that is fertilised by a certain type of wasp. The flowers inside the fig are unisexual and in modern plantations the male and female trees are kept apart for the sake of control and to increase the size of the crop. In cultural history, fig leaves have been used to cover the sexual organs of painted and sculpted bodies and the fruit itself is considered to be sensual with erotic undertones.The fig’s different associations and the artist’s impressions from the Galata area form the basis of the installation ”The Orchard of Resistance”, which deals with public space, lost paradise and patriarchal society.

Solo Exhibition: Finding the Edge

2017

Exhibition view: Galerie Nordenhake, Stockholm

Photo credits: Carl Henrik Tillberg

Thanks to Moa Brännström Ott, Jonas Dahlberg, Simon Goldin, David Larsson and Leonard Gustavsson Bokbinderi.

According to plate tectonics, the earth’s outer shell is divided into a number of large, rigid, moving plates that interact at their boundaries, where they converge, diverge, or slide past one another. Such interactions are believed to be responsible for most of the seismic and volcanic activity of the earth. Plates cause mountains to rise where they push together, and continents to fracture and oceans to form where they rift apart. The continents, sitting passively on the backs of the plates, drift with them, at the rate of a few centimeters a year. At the end of the Permian, some 300 million years ago, all the present continents are said to have been gathered together in a single supercontinent, Pangaea.

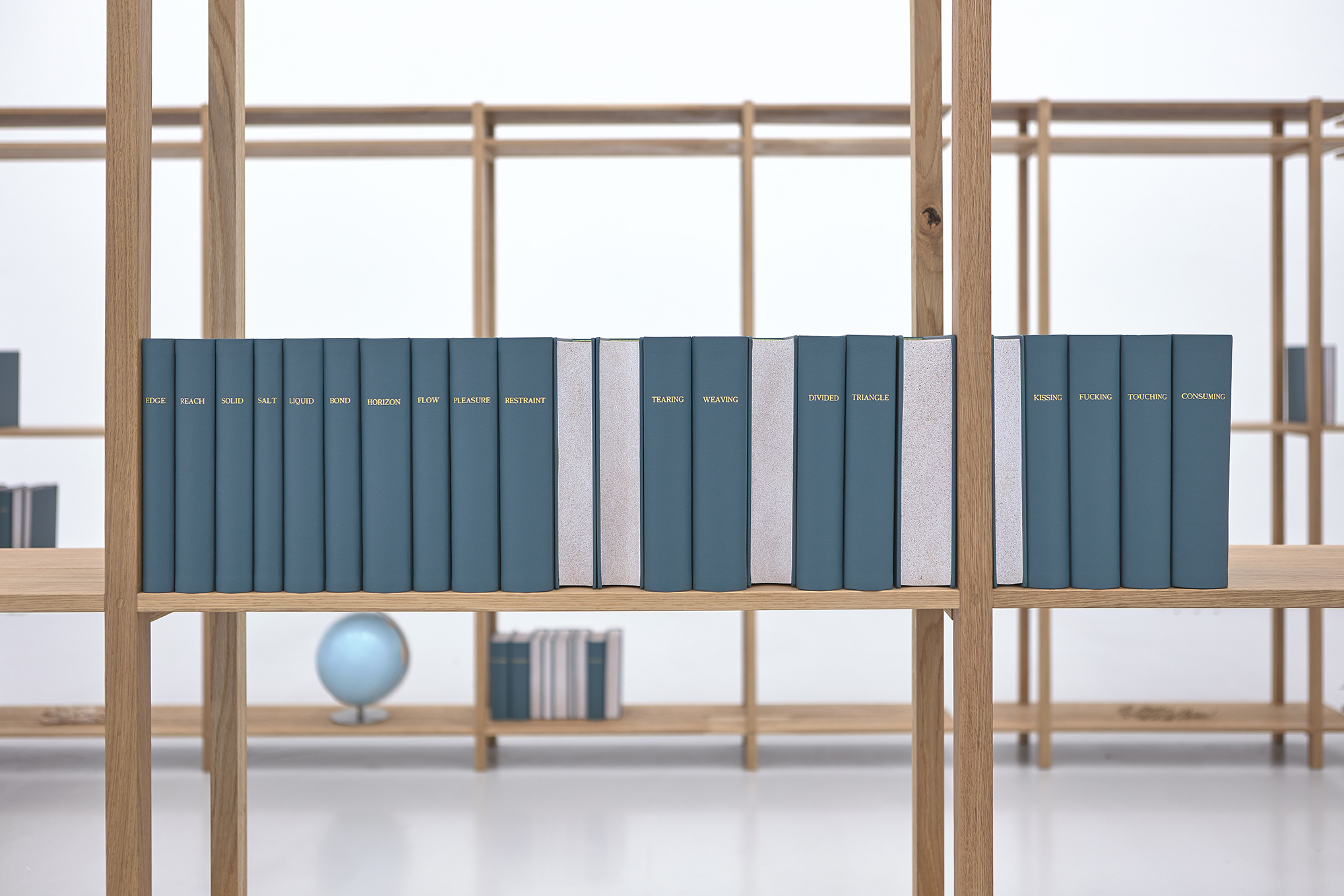

In her second solo exhibition titled Finding the Edge at Galerie Nordenhake Stockholm, Meriç Algün has made a series of new works that draws parallels between the separation of the continents and the origins of human desire. Algün’s investigation stems from the Canadian poet Anne Carson’s insightful book Eros: The Bittersweet (1983) where she speaks of love and desire as an issue of boundaries and separation. The frst room of the exhibition space is occupied by a freestanding shelving structure that is cut into seven units on site. The measurements of each unit correspond proportionally to the surface area of each continent, whilst the gaps between the rows of shelves correlate to the surface area of the oceans. In their self-contained logic, the shelves hold a variety of objects ranging from plants and animal fossils, to globes, hand made books, videos and sculptures that intertwine notions of geological and human boundaries and connections.

In the second room stands a conversation chair made in cherry wood and rattan. Whilst the chair is essentially designed to allow two people to face each other, it also separates them with the woven material through which they can only partially see each other. The work not only hints at the relationship between two people but also at the relationship between fragmented parts of a whole. Algün juxtaposes the chair with a wall text that is a short passage from a novel she is currently working on. The overall exhibition brings together her interest in understanding what drives people apart and what happens in the space that lies in between.

Promotion Europe

2016

Installation with 170 EU promotional items, 170 yellow plexiglass pedestals

Dimensions variable

Thanks to ARoS Art Museum, Lucas Odahara and Theodor Ringborg.

"Promotion Europe is made up out of 170 objects manufactured for the sake of branding, advertising, selling and in other ways encouraging the concept of the European Union. From ties and T-shirts, to nail clippers, shoe wax and neck massagers, these things brandish the 12 yellow stars of the EU against a recognizable blue background. Like souvenirs they are made to be objects of signification. Yet unlike souvenirs they don’t mark an elsewhere, but rather have something to do with constructing and enforcing an identity.

Europe and the rest of the world was once sold the concept of the EU, which meant unity, collaboration, openness and unwavering core beliefs along the lines of what’s generally taken for democratic. These objects, used for marketing purposes and so for the most part handed out for free, were meant to be infused with such ideals. Citizens clipping their nails with 12 star nail clippers would attest to a belief in EU and what it stood for. Yet with the recent near Grexit, the ongoing Brexit, the rise of the right-wing and the many seals suddenly put on supposedly open boarders, what do objects such as these things do now? They seem to speak of other conditions. Like Franco "Bifo" Berardi said not long ago, “The EU entity has been subjected to a sort of political directorate that has unfortunately only served to reveal that financial interests lie at the heart of the Union’s priorities.” Who would use the EU nail clipper now, and what would it say if they did?

This is not to say (not here at least) unequivocally that the EU was a good thing turned bad, but rather that to look at these things, en mass, is absurd, if not a bit grotesque. And so the real question with this piece is why is it so awkward to simply face these things? Why do they seem to embody something eerie? Is it a promise lost? Or is it perhaps because these vulgar things are EU history? Is it maybe because, though it’s difficult to trace each item to its exact origin, it is safe to say that what promotes Europe certainly wasn’t made in it."

/Theodor Ringborg

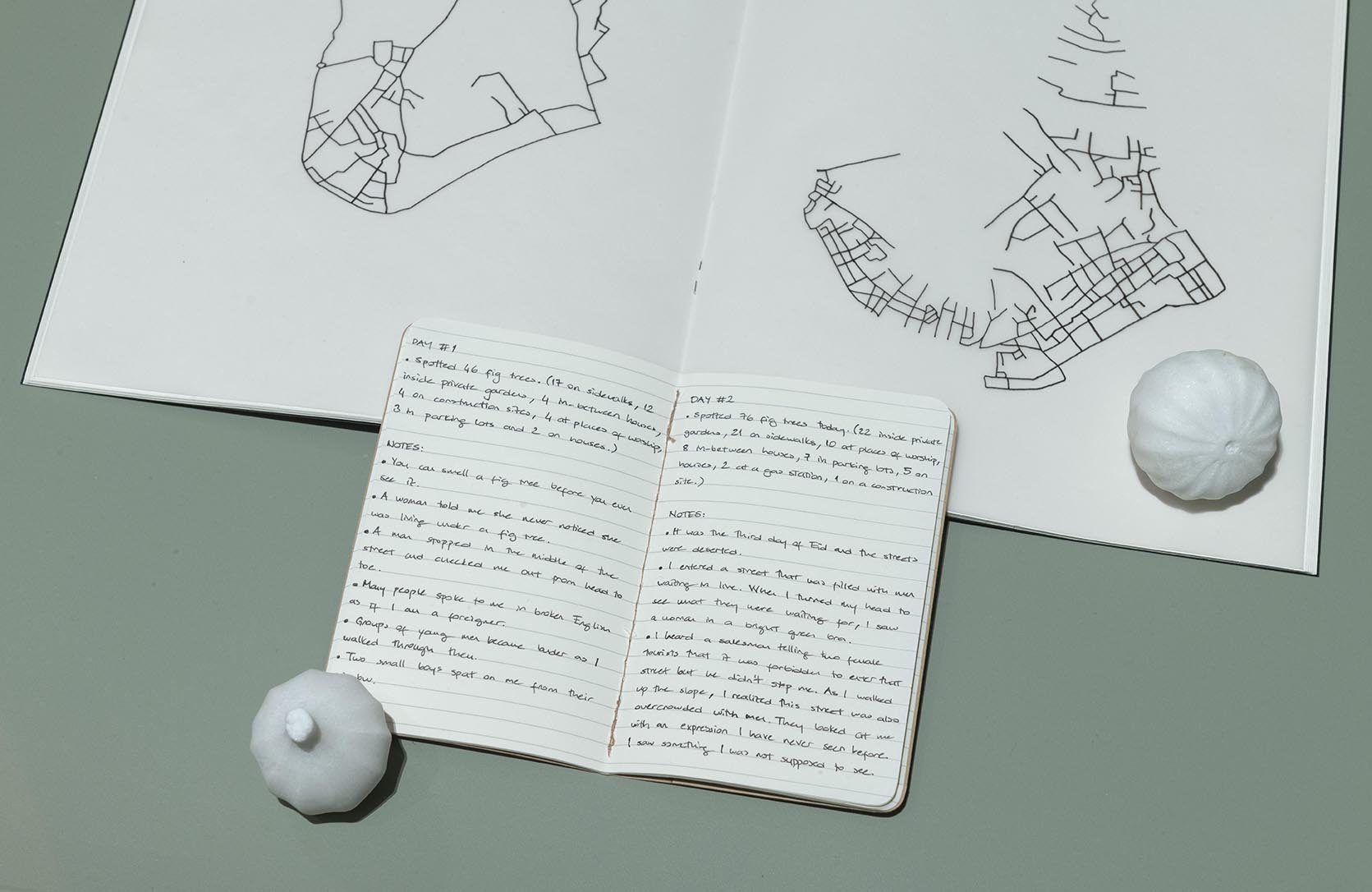

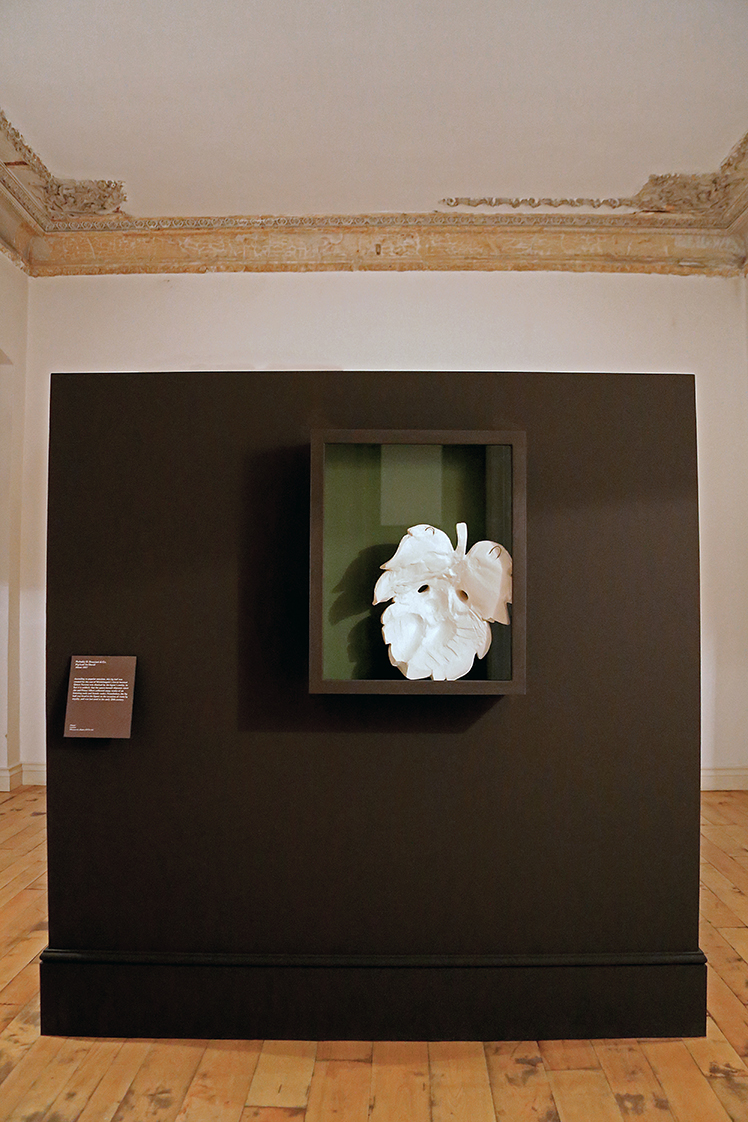

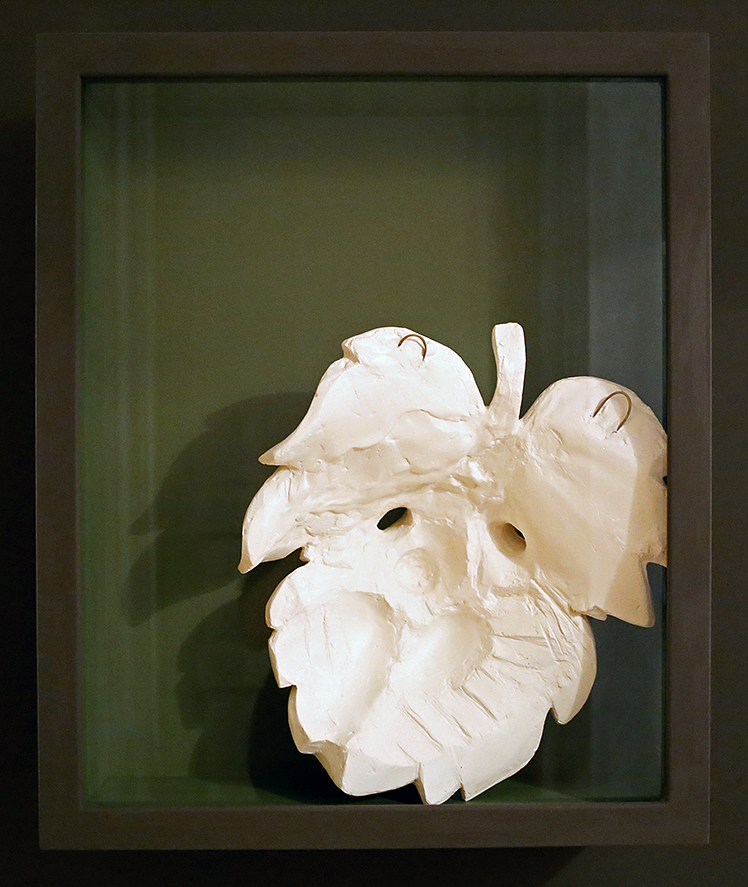

Have you ever seen a fig tree blossom?

2015

Site-specific installation, graphite drawing, plaster cast, fresco, video, fresh figs, marble, notebooks, slide show, dried fig leaves collected from local fig trees

Exhibited at Room 104B, Adahan Istanbul Hotel as a part of SALTWATER: A Theory of Thought Forms, 14th Istanbul Biennial, drafted by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev.

Produced with the support of Huma Kabakcı and SAHA – Supporting Contemporary Art from Turkey.

Thanks to Adahan Hotel Istanbul, Ebru Akıncı, IKSV, Kıymet Daştan, Robert Crosse and William Pettit & Candice Smith-Corby.

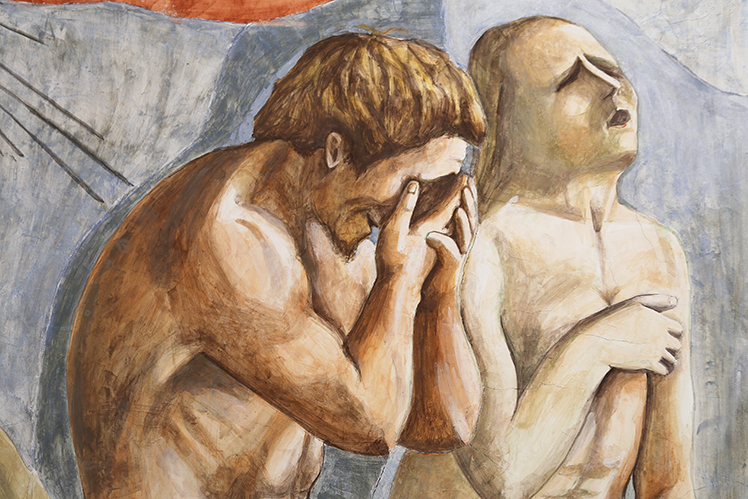

For the 14th Istanbul Biennial, Algün presents a site-specific installation around desire, sexuality and shame, titled Have you ever seen a fig tree blossom? in room 104B at the Adahan Hotel. Galata, previously called Sykai, used to be a fig orchard, its hillside covered with fig trees. Algün’s work is predicated on this orchard, the fig and the fig leaf, and takes the form of a constellation of gestures which underlines the gentrification processes occurring in Istanbul, and the destruction of its plant life. Also, it approaches the fruit as a symbol of female sexuality and the fig leaf as a symbol of shame. In the hotel room, she commissioned a copy of Masaccio’s fresco (1424–1425) of Adam and Eve’s expulsion from Paradise; in 1857, Queen Victoria refused a replica of Michelangelo’s David, and had a fig leaf made to cover his genitals. Yet fig trees are at the centre of two generative cycles: the intra-action between the female wasp and the female fig maintains the life cycle of the tree; while the female wasp to hermaphrodite fig relationship maintains the life cycle of the wasp. As the wasp crawls through the hole of the fig, she busts her abdomen, drops her wings and dies.

Souvenirs for the Landlocked

2015

Mixed media installation

210x600x720cm

Exhibition view: All the World’s Futures, 56th Venice Biennale

Photo: Gerhard Kassner

Thanks to David Larsson, Lucas Odahara, Konstnärsnämnden, SAHA Association, Theodor Ringborg and the Uçkun family.

My grandfather was as an operator on freighters traveling around the world. He traveled from the northern parts of Russia to Cape of Good Hope in Africa, from Brazil to Japan to Canada. He began working on ships right after his mandatory military service in Zonguldak, a city located in the Black Sea region of Turkey, when he was in his early 20’s and he worked until he got cancer at the age of 65. He had five daughters. And he met three of his five grandchildren. He was gone nearly every six months of the year so his presence was, and therefore the memory of him is, very fragmented. He brought gifts and souvenirs for each member of his family every time he returned, gifts that carried a particular significance with respect to an idea of an outside world due to the rest of the family being entirely landlocked.

Souvenirs for the Landlocked is an installation that both takes inspiration and uses the objects from my grandfather. However, it situates itself in a wider scope and regards also the longstanding history and growth of maritime shipping, which today carries 90 percent of the world’s 5.1 billion tons of international trade. The career of my grandfather followed the burgeoning rise of maritime transport on an industrial scale. As he began to work at sea in the 1950’s, dry cargo and tanker cargo amounted to a total of 460 tons. By the mid-nighties it was 4,687 tons due in part to containerization, the development of the modern intermodal container and its standardization. This is a project that seeks to understand the mobility of such trade and the mobility of those that travel with it, amongst them my grandfather, and it does so by looking toward shipping routes, the perils of sea, and the physicality of bringing things from one end of the world to the other. Yet it’s also a work that considers the condition of being immobile, the metaphorical landlockedness of the family at home.

The installation comprises a group of sculptural works placed within an environment. This environment aims to hybridize the contexts of ship and home, referring to an idea of being both mobile and immobile. It works toward a paradox of existing in two incompatible places at once (and perhaps two incompatible conditions), making up a disorienting synthesis. Merging the spheres of ship and home as a framework, this ambiguous space amplifies a tension that speaks of a kind of presence neither wholly there nor completely absent, but rather found in some sort of uncharted in-between. This hybrid room is minimal in tone and constructed by laying a metal floor that calls to mind a ship’s deck, the modern kind, painted in a cargo ship’s typical antifouling red paint, all to allude to the idea of a ship.

The way that the context of home is manifested in this space is through the form each sculpture takes. One of these sculptures is a display case of the type many might have at home, typically to show cherished objects. Inside are the souvenirs my grandfather brought back from his travels. My interest in the souvenirs comes from their position between “the site of being away” and “the place of being home”. A souvenir is a signifier of “somewhere else” affixed into the context of home, taken from a foreign place to a familiar one with the intention that it links back to its origin. And it’s obtained to exemplify the difference. Thus, souvenirs present an alterity that is relative to normative home, locating it in the space that separates the “site of being away” and “the place of being home”. But not only do they signify the threshold between localities, the souvenir also offers proof of mobility and thus connotes shifting positions of the subject. Souvenirs are representative of what ‘has been seen’ and thus echo a highly subjective sight, much like photographs; albeit contrary to an image they are sculptural representations of experiences, markers of the transference from event to memory. They are things the subject can recite, things around which the subject can, rather than show, tell the story of travel.

Another part of the installation is a dual-door cabinet onto which an image of a ship is represented by the technique of intarsia across its two doors. The cabinet is overfilled with fine china in such a way that the cabinet’s doors are slightly opened, and the ship ‘divided’ by way of the gap in the doors. The cabinet alludes to a shipping container, and by filling it beyond its capacity so that the ship breaks in half brings to mind the instances when this has occurred. When my grandfather was out to sea there was never guarantees that he’d return. And with the growth of the shipping industry, the increased demands on quantities and time of delivery, people are forced into taking great risks and thus face greater and greater perils.

Another piece is a pedestal on which a vase with fresh flowers stand. It is a piece that suggests ways in which things are linked and transported, but also a kind of fiction of transporting things. Going through my grandfather’s material I came across a booklet titled “Marine Radio Officers, Rates and Information Manual”. In it, aside from information on frequencies etc. is information on a gift service for shipping flowers, as the booklet says “from ship-to-shore”. The service is provided by FTD, Florists’ Transworld Delivery; a company that still provides this service. Of course, the flowers aren’t “from ship-to-shore” and herein lay the fiction of this transport. On the pedestal there is a card with FTD’s logo, as “Transworld” here is significant. Moreover, the flowers are a testimonial to a relationship between ship and shore, as if a message in a time before instant communication.

Yet another piece is a custom-made globe that maps all shipping routes in the world. In the interlocking web these shipping lines create, 90% of everything is shipped by sea. Total seaborne cargo movements exceeded 21 trillion ton-miles (a unit of measure- ment equivalent to a ton of freight moved one mile) in 1998. Modern container ships carry a forty-foot container for less than 10 cents per mile – a fraction of the cost of surface transport. The map, thus, is an entangled web of lines and shows a particular topography. It reveals a contemporary interconnectivity predicated on a physicality seldom reflected upon. It is a geopolitics of currents, trade-winds and shores. A globe with only shipping lines visible creates a new sense of the world and a new sense of geography and the labor that takes place at sea. Alongside this globe there is an oil lamp standing on a small table which concerns the fact that the most shipped commodity is crude oil. It references oil as a perishable, continuously re-shipped commodity as well as it alludes to the contemporary dependency on it. Here the oil lamp is placed on a doily with a pineapple pattern. Aside from the doily as a craft technique referencing home and the landlocked, my grandfather once brought home, as a souvenir, a pineapple. However, no one in the family knew how to cut it open and so it perished. Pineapples, like crude oil, are shipped expansive stretches because they aren’t to be found in parts of the world. And today’s near ubiquitous recognition of the fruit is telling of the development of transportation. It is a shift from being exotic to typical. Furthermore, pineapples used to be used as signs of sailors returning home. A sailor would put it outside their homes to indicate homecoming. Perhaps this is why my grandfather once brought one. Moreover, like oil, for it to be re-stocked in the supermarkets of northern Europe and America, it is accumulated and transported continuously and so a seeming separation between crude oil and a pineapple shrinks in the sphere of shipping.

/Meriç Algün

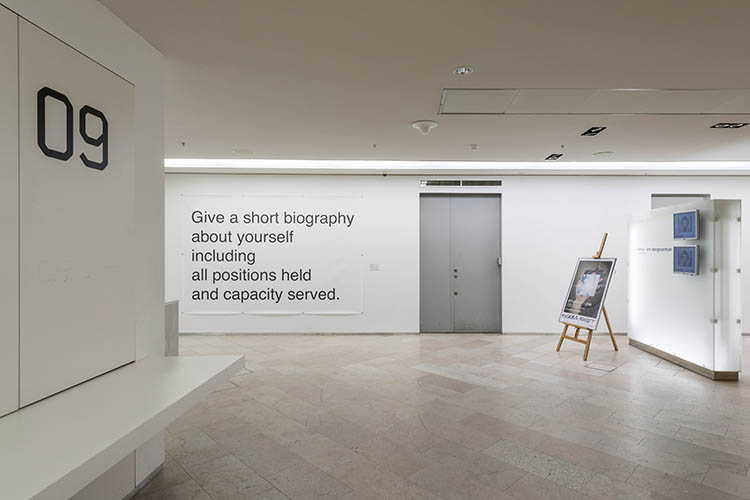

Solo Exhibition: Becoming European, Moderna Museet, Stockholm

2014

Photo: Åsa Lundén, Moderna Museet, Stockholm

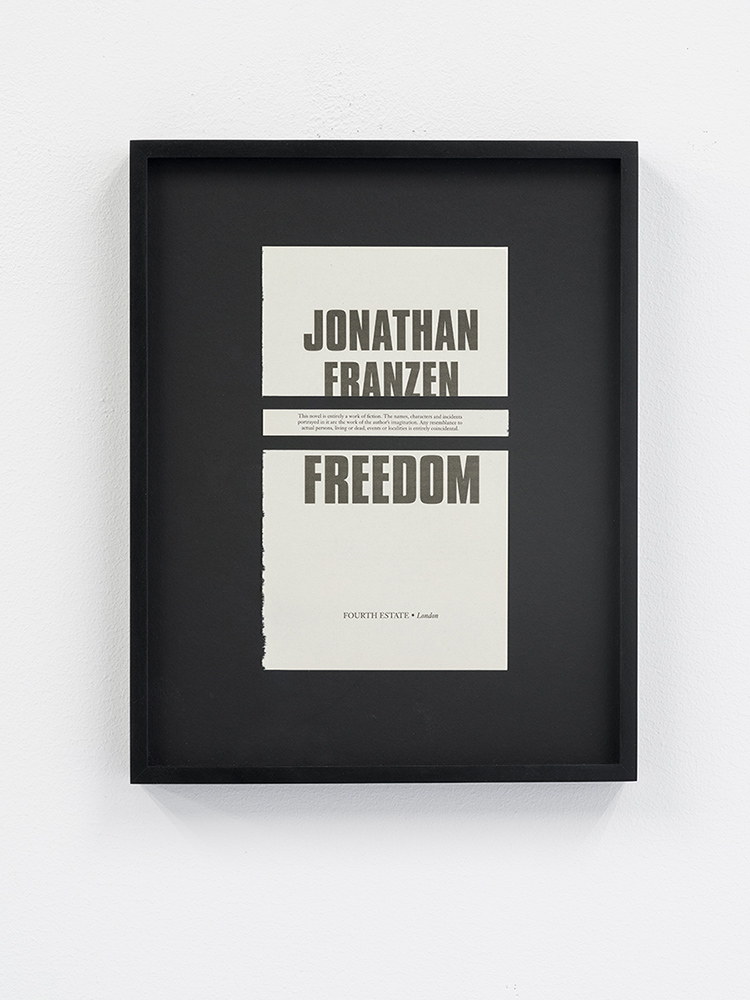

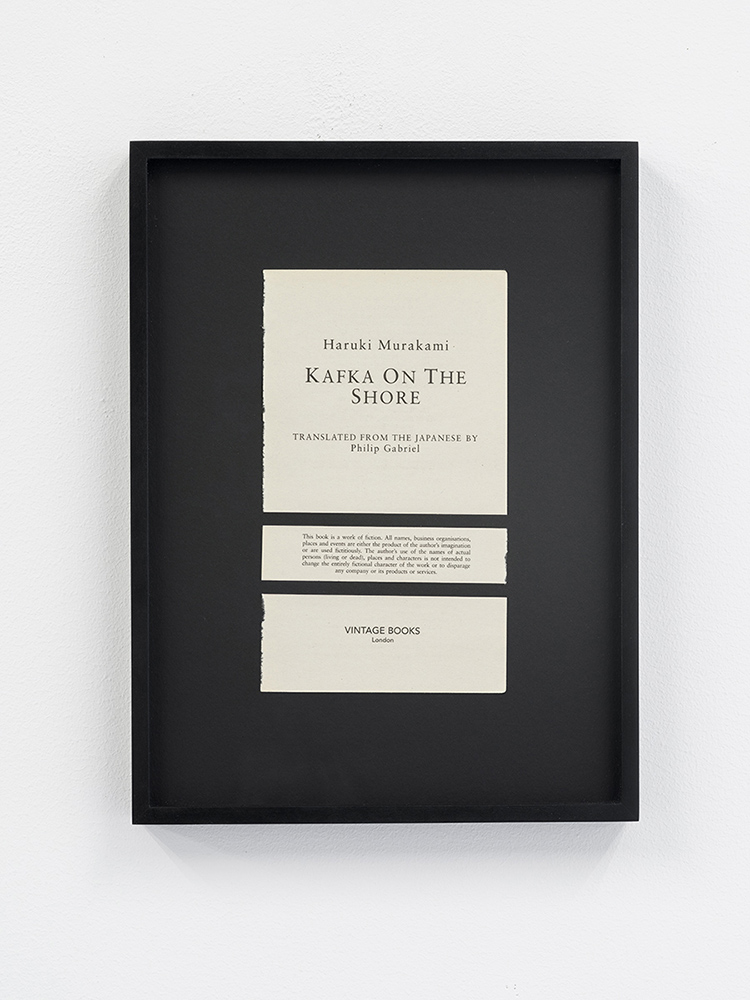

Disclaimers

2014-

Series of collages

Dimensions variable

Photo: Gerhard Kassner

A World of Blind Chance

2014

Video

32'27''

Thanks to Michael Nyqvist, Nils Fridén, Velourfilm AB and Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

A World of Blind Chance, is a play in three acts, where the script is composed by found sentences from the Oxford English Dictionary. Each act consists of an actor character entering the stage where he is rehearsing a monologue; a philosophical rambling on subjects such as acting and being on stage, representation of time and space, the search for truth and essence of existence, language, chance and the origin of

the universe. Whilst the actor is performing his lines, his movements are directed by the author’s voice.

Men in Buckram

2014

bookbinding buckram

65x65 cm each

Photo credits: Gerhard Kassner

Men in Buckram is a series of monochromes made with buckram, a coarse linen stiffened with gum or paste, used for bookbinding. The buckrams come from Leonard Gustafssons Bokbinderi, Stockholm, which was founded a century ago. Each title corresponds to the number of the buckram in the catalogue found at the atelier. Buckram, aside from being a material, at the same time refers to the phrase ‘men in buckram’, originating in Shakespeare’s Henry IV, defined to mean “hypothetical men existing only in the brain of the imaginer”.

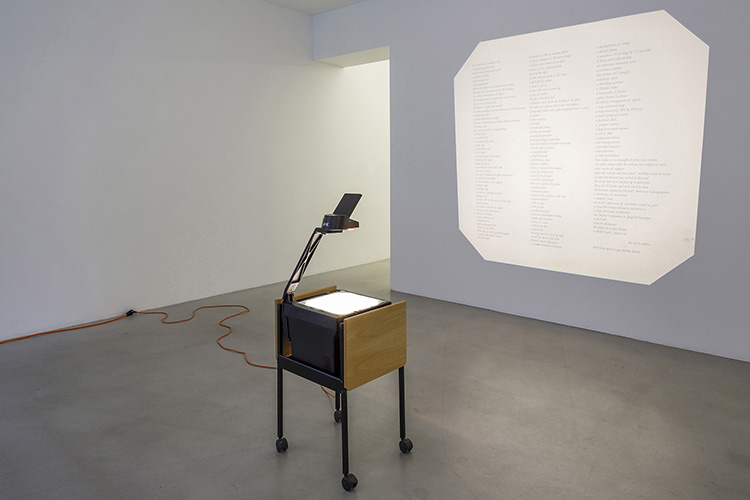

A Work of Fiction

2013

Installation with found objects, videos, sound

Dimensions variable

Solo Exhibition at Galerie Nordenhake, Stockholm

Photo: Jean-Baptiste Béranger

A Work of Fiction is an installation reminiscent of an author’s space and it is created as a framework to a body of text based works generated through a constrained writing methodology: by strictly copy-pasting sample sentences found in the Oxford English Dictionary.

The installation begins with a list-like description of itself presented on an overhead projector, and then is manifested in the space through furniture, objects, and general ephemera that belongs to the apparent author. The list also describes the artworks in the space. Placed on a coffee table, for instance, lies the manuscript of a short novel. The 24-page A Work of Fiction (Manuscript) (see below) assembles found sentences into a seemingly conventional narrative and adopts the style of a generic romance, thriller and mystery tale. The story follows the characters Mark, Maria and Peter whose relations evolve into drama, unfaithfulness and murder. Whilst the constrained writing technique creates a story guided by circumstance, it could at times be mistaken for a story written unrestricted. A recording device on the author’s desk plays the self- reflexive narrative Metatext (see below). As the author reveals their principles of creation and process of writing, the narrative meanders, eventually loops and turns in on itself. Furthermore in the space, two silent videos titled Infinity and Eternity (see below) focus on hands performing meditative and repetitious tasks; one of which is to tie a decorative knot, the other to perform a trick with a pen. Both pieces bring up a notion of purposelessness, as a decorative knot serves no use as a knot and a pen trick is an act performed in the interim of writing.

Excerpt from the list of objects:

the gallery was a single large room

walls were painted with white

fluorescent lights are mounted on the ceiling

the arrangement of the furniture in the room more or less symmetrical

the decor is simple and tasteful quality furniture

...

an old sofa

a low table

a secret drawer in the table

the top of the table

an authentic document

a work of fiction

a strong blue color

a headline in thick black type

a couple of spelling mistakes and typing errors

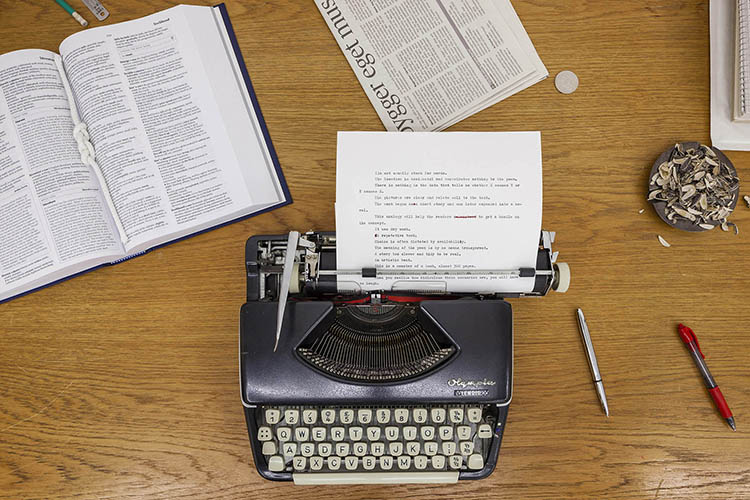

A Work of Fiction (Manuscript)

2013

Typewritten manuscript, handbound cover

A4-format, 24 pages, cover: 22x31 cm

Photo: Jean-Baptiste Béranger

The 24-page A Work of Fiction (Manuscript) assembles found sentences into a seemingly conventional narrative and adopts the style of a generic romance, thriller and mystery tale. The story follows the characters Mark, Maria and Peter whose relations evolve into drama, unfaithfulness and murder. Whilst the constrained writing technique creates a story guided by circumstance, it could at times be mistaken for a story written unrestricted.

Metatext

2013

Audio

13'13'', seamless loop

Photo credits: Gerhard Kassner

Click here to listen to Metatext

Metatext is complied by sample sentences found in the Oxford English Dictionary and voiced by a fictitious author, who only writes with this constrained method. The piece concerns the role of language in the act of writing and artistic creation and explores ways of expression without having total freedom. Here the sentences are divorced from their original intent and assembled into a seemingly meaningful account, where the author speaks of her process of writing, her motives and ambitions. Eventually the narrative meanders, loops and turns in on itself.

Algün’s method, grounded in applying rules and constraints to literary production, has been loosely associated with Oulipo – a group of French writers and mathematicians who sought further meaning in literature, by imposing multiple restrictions on the process of writing. By exploring our relationship to language, extracting texts from their original meaning and reinterpreting them, the role of the artist and the notion of authorship are challenged.

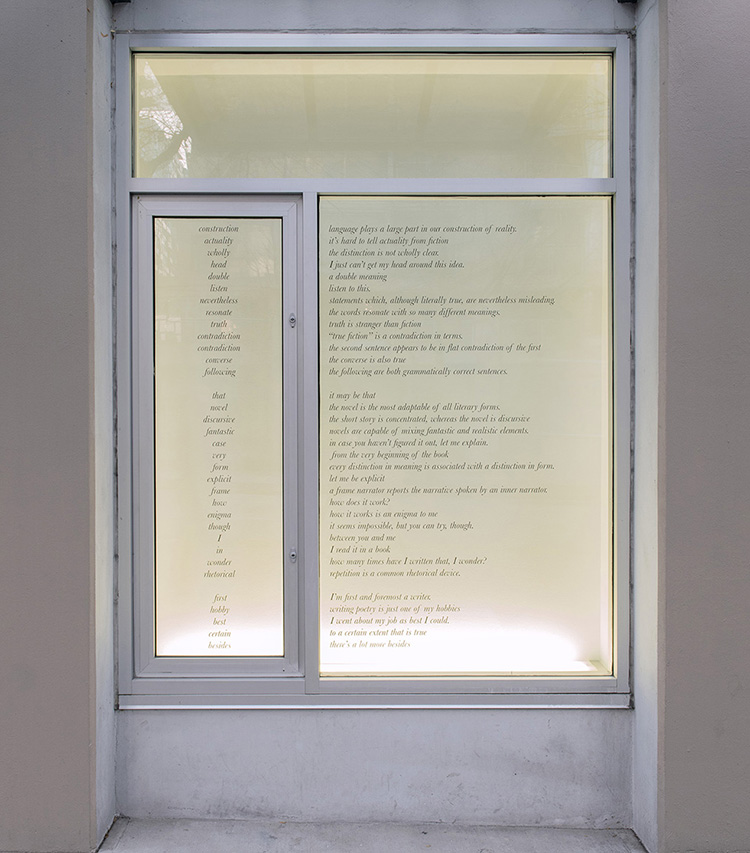

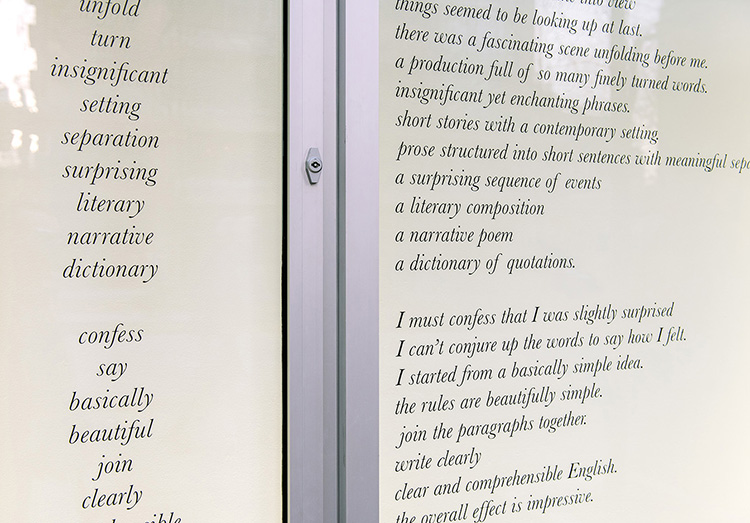

Metatext (for Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver)

2013

site-specific, vinyl text on glass

9 windows, each wide window: 178x109 cm, each narrow window: 167x47 cm

Photo credits: Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver

Eternity and Infinity

2013

Video installation with palm trees

Duration: 11'34'' and 12'19'', loop

Photo: Jean-Baptiste Béranger

Click here to watch excerpts from Eternity and Infinity

Infinity and Eternity focus on hands performing meditative and repetitious tasks; one of which is to tie a decorative knot, the other to perform a trick with a pen. Both pieces bring up a notion of purposelessness, as a decorative knot serves no use as a knot and a pen trick is an act performed in the interim of writing.

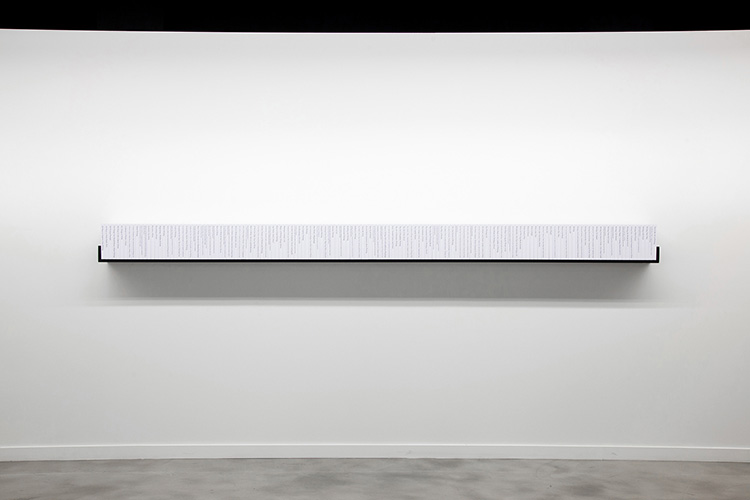

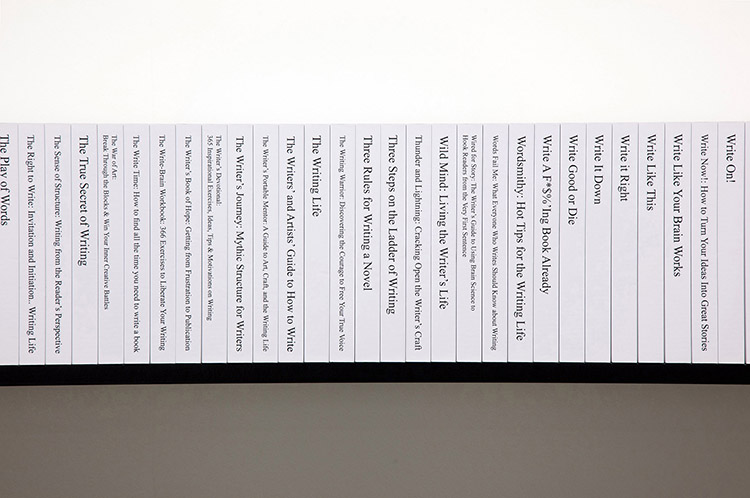

On Writing

On Writing

2013

150 blank books on black valchromat shelf

330x21x15cm

Photo: Serkan Taycan

On Writing comprises one hundred and fifty titles of self-help books on writing printed as blank books. Titles like "How-To Write", "Write or Die", "Becoming a Writer" and "No Plot? No Problem!: A Low-Stress, High-Velocity Guide to Writing a Novel in 30 Days" come to signify the act of writing and its difficulties, referencing simultaneously that nothing written here has been ‘written’ at all. Writing comes to be synonymous with creating, the making of something, which in this case might mean art. It shows the struggle, with humor. The many guides to creativity aim at producing, giving tips and tricks on how and what to write but rarely are they concerned with what it actually might mean to make, write or author something. One is simply supposed to know "How to Write and Sell a Novel", which ultimately also hints at the market of "how-to-write" books and the abundance and variations in which they come, and by extension also the many want-to-be authors who consider the first sentence so hard to compose.

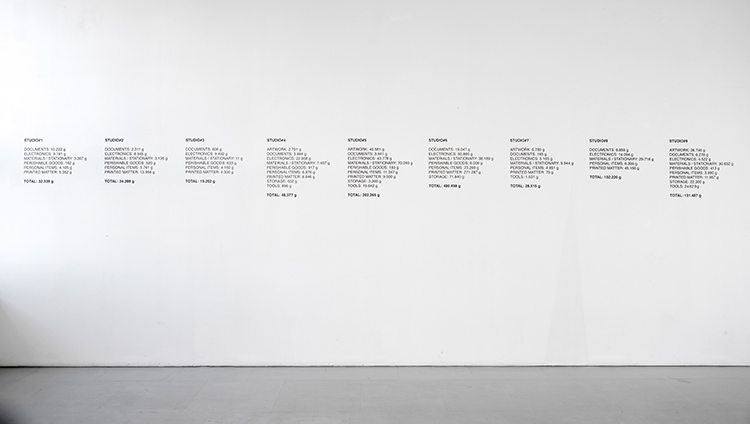

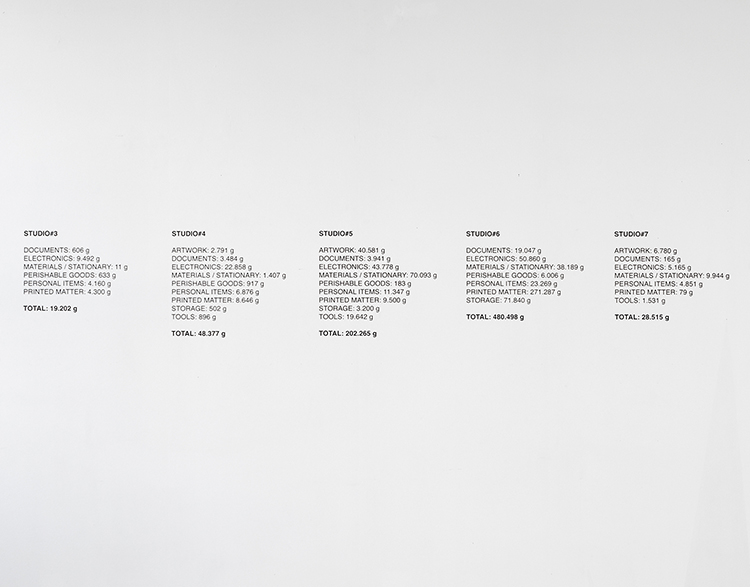

The Weight of IASPIS

2013

site-specific, vinyl text on wall

Exhibition view: IASPIS (The Swedish Arts Grants Committee’s International Programme for Visual Artists) Open House, Stockholm.

Photo credits: Jean-Baptiste Béranger

Line No.3 (Holy Bible, Selkirk and Crusoe)

2013

Print on transparent vinyl, wall drawing, varnish, audio

Dimensions variable, audio duration: 10'18''

Exhibition view: Signs Taken in Wonder, MAK, Vienna

Photo credits: Katrin Wißkirchen

Click here to listen to an excerpt from Line No.3 (Holy Bible, Selkirk and Crusoe)

In the work Line No.1 (Holy Bible), first presented at Index, Stockholm, two authoritarian components were integrated, a line and the Holy Bible in an attempt to raise questions on constraints, borders and control. With the work’s second installment, Line No.2 (Holy Bible) at Witte de With, Rotterdam two additional components that originated from the islands that are named after Selkirk and Crusoe in the archipelago of Juan Fernández on the coast of Chile were incorporated. Selkirk’s island neighbors Cruose’s and by tracing the borders of both islands from Google Earth images onto two large walls in the middle of the room, surrounded with the Bible, the facts of Selkirk and the fiction of Cruose meet. With the piece’s third installment Line No.3 (Holy Bible, Selkirk and Crusoe) at MAK, Vienna, a final component has been developed. A sound-piece composed out of the borders of Selkirk and Crusoe islands. The sound permeates the room as a measure of speech, or perhaps the lack thereof. As an abstracted means of communication, both of language and of the borders of each island.

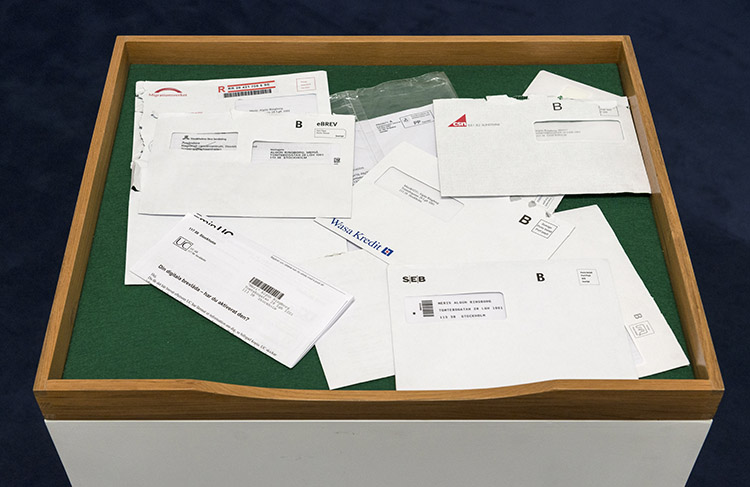

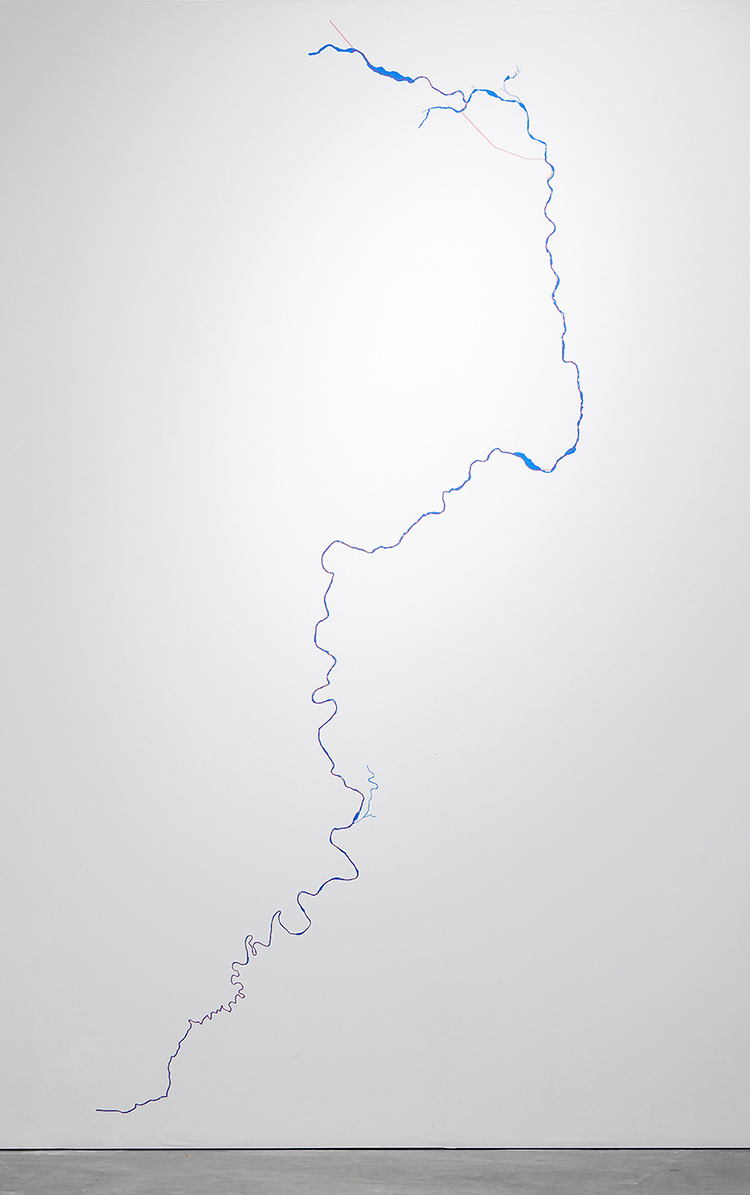

A Hook or a Tail

2013

Series of works

Dimensions variable

Exhibition view: Marabouparken, Stockholm.

Photo: Jean-Baptiste Béranger

Click here to listen to an excerpt from Archiving Meriç

In the series of works A Hook or a Tail, Algün explores the manners one can move across borders. One way is the manner in which Algün herself moved from Istanbul to Stockholm, entailing bureaucratic stamps, application forms and interviews, which ultimately might result in a lawful and legal residence within the EU. The other manner, of course, is to move illegally. On this occasion the border is more specifically the river Meriç, or Evros or Maritsa. Originating from Bulgaria, it acts as the border between Turkey and Greece and is given different names respectively. The river, partly being the namesake of the artist, is today one of the most frequently used locations for illegally entering the European Union. That the artist shares her name with this river is coincidental, but nevertheless intriguing, and the river being the river Meriç is central to these works.

Algün looks at the river itself, and by its simple image or topographical outline suggests the notions of crossing it in either direction. Taking its reference from Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ “Untitled” which is an endless reproduction of an image of water, Algün shows an image of the Meriç river in a similar manner. In Untitled (Evros, Maritsa, Meriç) she hints at the different localities that surround this water and therefore the different political systems they exist within. Furthering this idea, in the work Blue River Red Border two lines mark the bird’s eye view of the river and the border. It was decided at the treaty of Lausanne how the border and river would coalesce, but as it meanders, the piece shows where the river flows naturally and where the treaty of Lausanne once decided that the border would run. Simultaneously presenting their similarities and differences shows places where they act as a unity and places where they diverge, and the fiction of the border, its made-upness from a political treaty, and the consequential inside and outside that the river marks is made apparent.

Ç (The Unfortunate Letter) is a collection of personal letters that concern the mark known as cedilla, as in the c of Meriç. In the artist’s new context of Sweden, the ç is frequently confused or altered in letters from authoritative agencies such as banks, universities and even the Migration office. Ranging from simply omitting the letter and making the name Meri to more advanced Meri% to replacing the ç with the html code as in Meri& #231; the loss of the cedilla serves as a continuous reminder of ‘originally’ coming from somewhere else and of not fitting within the system. Moreover, Archiving Meriç, a sound piece plays numerous individuals saying Meriç with varied pronunciation, which simultaneously and confusingly is either the artists’ name or the name of the river, or both – blurring the boundaries of the two and making central the name no matter what or whom it is attached to. The ç comes to act as the symbol, both literally and metaphorically, of being transboundary.

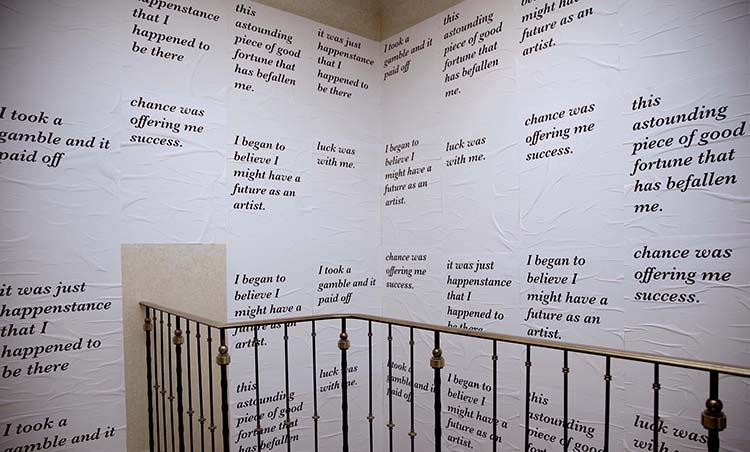

successes, failures and in-betweens

2012

Screen print on recycled paper

Each print 50x70 cm, installation dimensions variable

Photo: Amir Guberstein

The work successes, failures and in-betweens is made specifically for the “Memory of Present” exhibition organized by coup de dés. The work is formed by phrases that are used in the English dictionary to exemplify how a particular word is used in a sentence. The keywords originate from the exhibition’s concept on roll of dice, chance, luck and fortune.

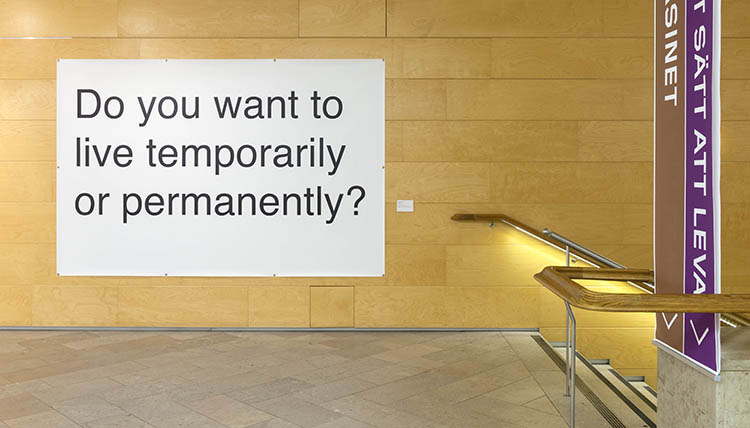

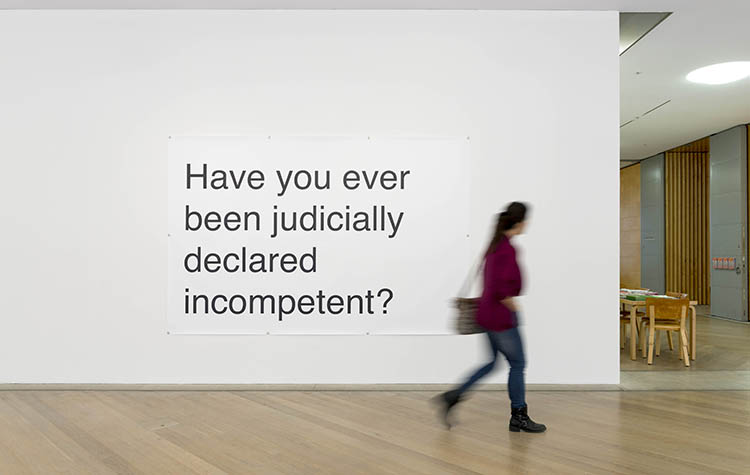

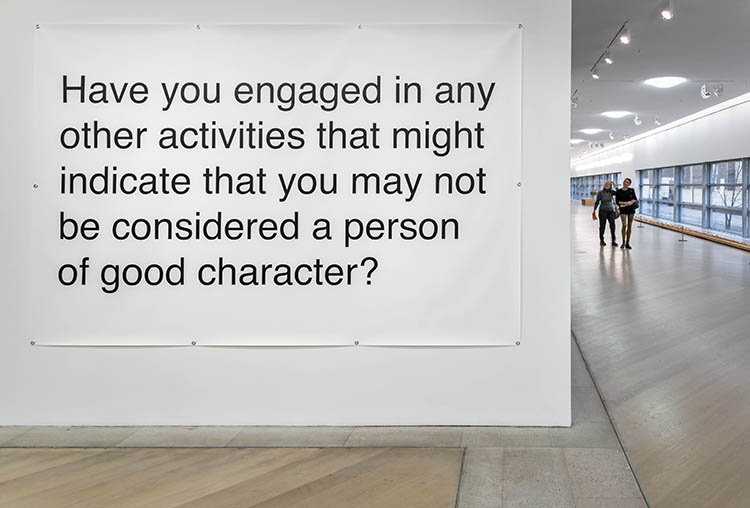

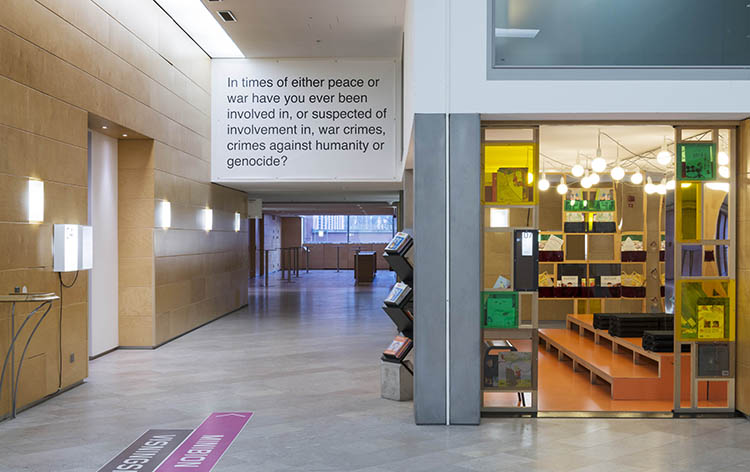

Billboards

Billboards

2012

Photo: Anna Granqvist

Billboards are a series of works that present a selection of the inquiries found in visa application forms. The displacement of these questions, such as “Are you and your partner living in a genuine and stable partnership?” or “If you reside in a country other than your country of origin, have you permission to return to that country?” underlines the invasiveness of the queries and, in turn, questions the questions themselves. These billboards have initally been made for the “Show Off” exhibition curated by Jacob Fabricius, that took place in Malmö and Nicosia respectively.

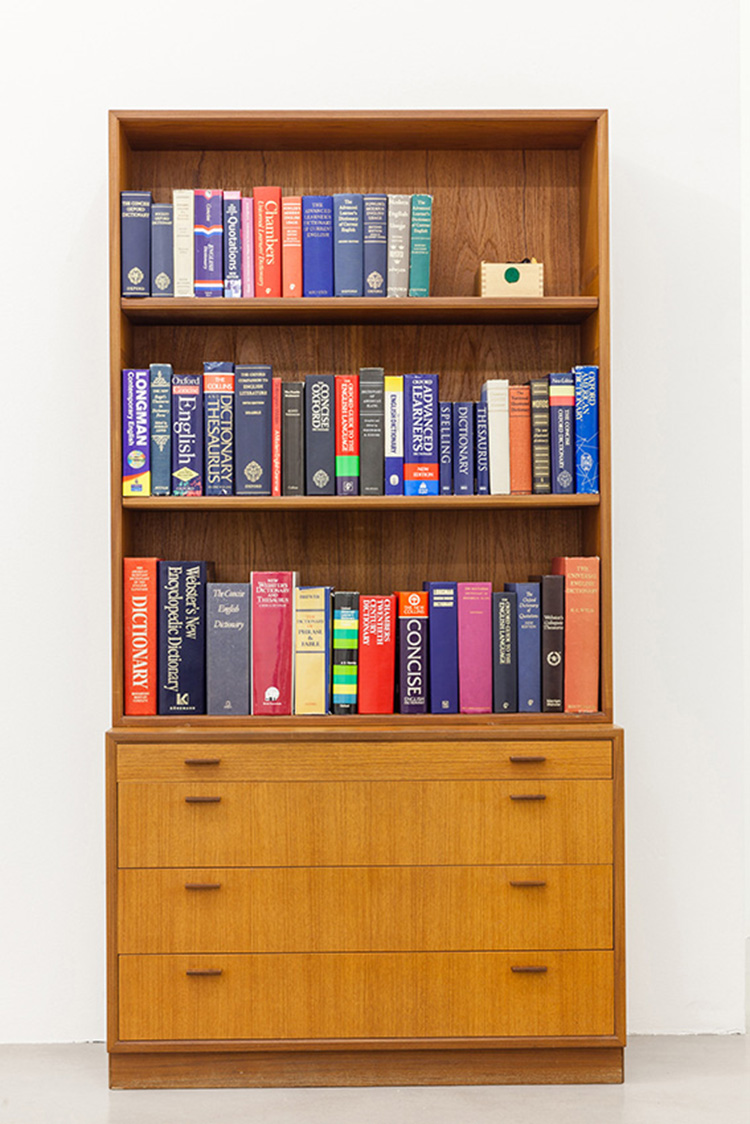

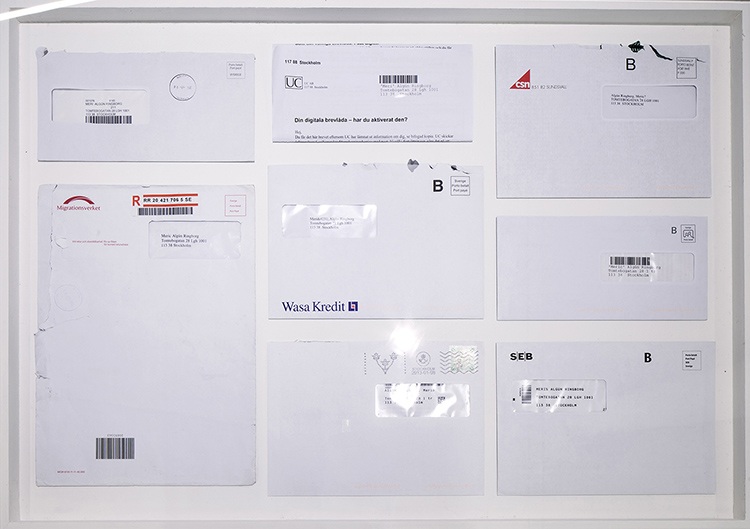

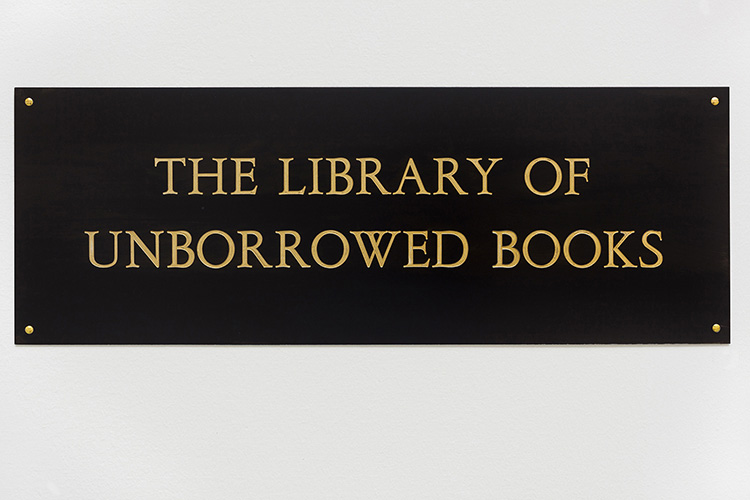

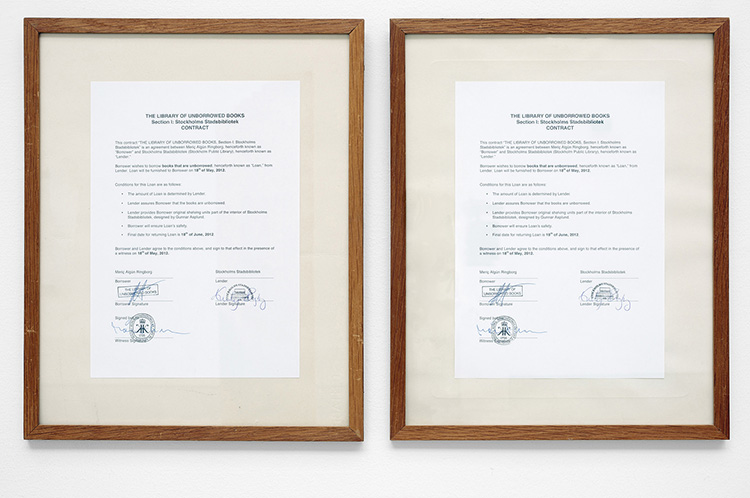

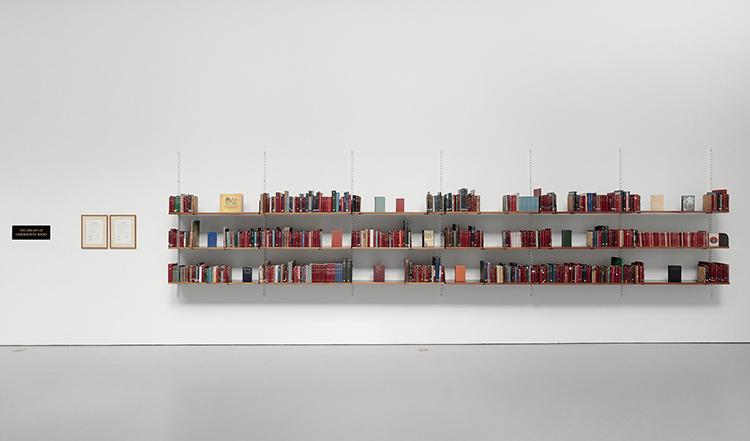

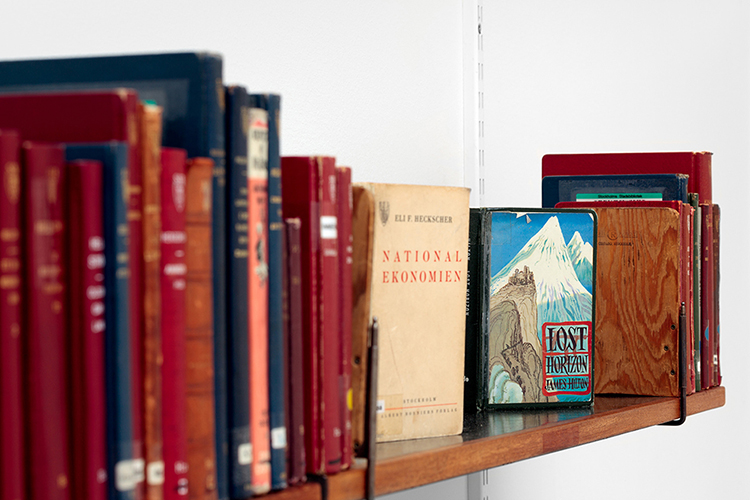

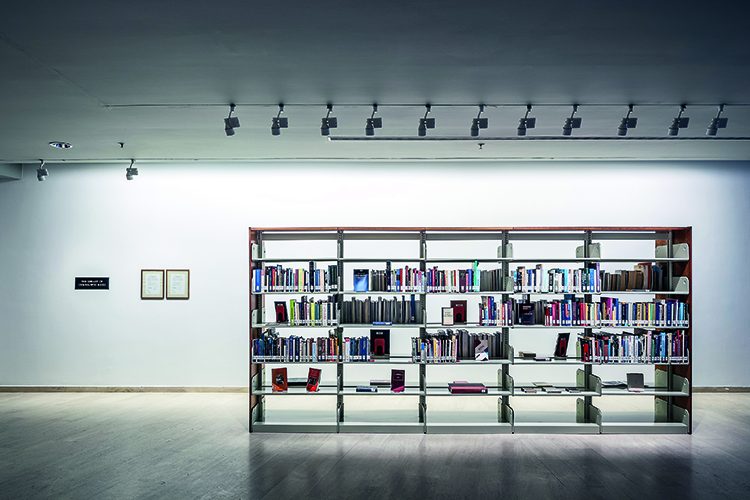

The Library of Unborrowed Books, Section I: Stockholms Stadsbibliotek (Stockholm Public Library)

2012

site-specific installation with books, shelves, brass sign, two contracts

Exhibition view: Konstakademien, Stockholm

Photo: Jean-Baptiste Bérangere

The Library of Unborrowed Books, Section II: Center for Fiction

2013

site-specific installation with books, shelves, brass sign, two contracts

Exhibition view: Art in General, NY

Photo: Art in General, NY

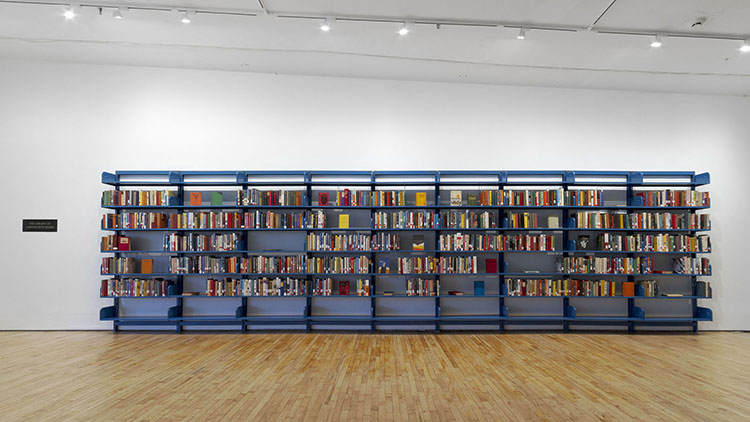

The Library of Unborrowed Books, Section III: Sydney Mechanics’ School of Arts Library

2014

site-specific installation with books, shelves, brass sign, two contracts

Exhibition view: 19th Biennale of Sydney

Photo: Gunther Hang

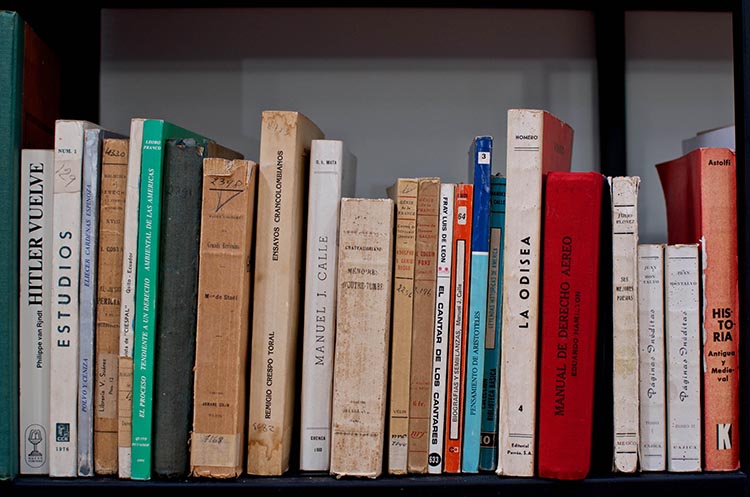

The Library of Unborrowed Books, Section IV: Centro de Documentación Regional “Juan Bautista Vázquez”

2014

site-specific installation with books, shelves, brass sign, two contracts

Exhibition view: 12th Cuenca Biennial

Photo: Cuenca Biennial

The Library of Unborrowed Books, Section V: The Gennadius Library, ASCS, Athens

2014

site-specific installation with books, shelves, brass sign, two contracts

Exhibition view: The Gennadius Library, ASCS, Athens

Photo: Neon Foundation, Athens

The Library of Unborrowed Books, Section VI: Sabancı University Information Center, Istanbul

2015

site-specific installation with books, shelves, brass sign, two contracts

Exhibition view: Sakıp Sabancı Museum, Istanbul

Photo: Murat Germen

The Library of Unborrowed Books, Section VII: Universitetsbiblioteket, Lunds universitet

2017

site-specific installation with books, shelves, brass sign, two contracts

Exhibition view: Kungshuset, Lund

Photo: Joakim Stierna

There is a selection made of what books accompany us into the future. Within education, for instance, the establishment of a canon is clear – it is the venue for the particular echo that determines what books persevere, those that are to be kept in the loop and read again by the next generation. This comes natural, a selection is necessary, and it’s made in different instances either conscious or unconscious. Nevertheless, the books that are left behind — those deemed useless or for unknown reasons are abandoned — still exist in physical form, organized and systematized within the one institution representative of knowledge in all its forms, the library.

The Library of Unborrowed Books bases itself on the concept of the library as an institution manifesting language and knowledge, of the passing of awareness and the openness to all types of people and literature. This work, however, comprises all the books from a selected library that have never been borrowed. The framework in this instance hints at what has been disregarded, knowledge essentially unconsumed, and puts on display what has eluded us.

Why these books aren’t ‘chosen,’ why they are overlooked, will never be clear but whatever each book contains, en masse they become representative of the gaps and cracks of history, or the bureaucratic cataloging of the world, the ambivalent relationship between absence and presence. In this library their existence is validated simply by being borrowed, underlining their being as well as their content and form by putting them on display in an autonomous library dedicated to the books yet to have been revealed.

Line No.2 (Holy Bible)

2012

Print on transparent vinyl, wall drawing, varnish

Dimensions variable

Exhibition view: Witte de With, Rotterdam

Photo: Bob Goedewaagen

An interview with Meriç Algün about Prompts & Triggers: Line No.2 (Holy Bible) 2012, at Witte de With from 26 April – 17 June 2012.

Defne Ayas (DA): What is it that you have found so fascinating in the relationship between Selkirk, Crusoe, and the Bible?

Meriç Algün (MA): When I first started reading about Selkirk, I was immediately drawn to the fact that the only book he had when he was marooned on ‘his’ island was the Bible. It was the only book he had to read for four years and four months, and within the shores of his isolation it spurred an immense personal transformation. Daniel Defoe, in turn, based his character Crusoe on Selkirk’s story, which he had heard from Woodes Rogers, the captain of the ship that saved Selkirk from his island. This transformation of stories as they are being told and retold and the meanings that are lost and found is similar to how religious texts were written and interpreted historically, as well as today. I wanted to work with this relationship by way of transforming the Bible itself into an inescapable horizontal line.

DA: Could you talk more about the special role that the Bible plays in the life of Selkirk and also Robinson Crusoe?

MA: Selkirk is said to have been a very bad mannered person before he ended up on the island—apparently this was the reason he was thrown off the ship he was sailing with in the first place. After years of being alone, he is said however to have become a better man. Indeed, one could presume, since it was his only resource, that the Bible caused this shift, but there are also accounts that Selkirk simply used the Bible, not as a religious text but as any text, and read it out loud to himself to maintain his command of language. With Crusoe it is a different story. Defoe made him a religious man before he became a castaway. But, actually, the most significant difference from Selkirk is that Crusoe was not alone: he had his companion Friday, who, in a defining moment of ‘triumph,’ he converts to Christianity. With Selkirk it is an individual experience of the Bible that’s muddled by varied, conflicting accounts, but in Robinson Crusoe the didactic and authoritative use of this text becomes more visible.

DA: Why did you choose to work with the King James Version of the Bible?

MA: All the biblical quotations in Robinson Crusoe came from the King James Bible of 1611. This version was the third English translation, and it is basically the most common and accepted one in a contemporary sense. If you look at a translation time-line of the Bible, this version was when its language becomes more consistent. For instance, the King James Bible was to solve all the translation problems that were foreseen by the Puritans. As a matter of fact, Daniel Defoe was a Puritan, thus also the character of Robinson Crusoe.

DA: How would you connect this to today, if at all?

MA: One example could be the particular role that scriptures written centuries ago have in contemporary politics. To illustrate this contemporary influence, one can look at how, just a few years ago, each daily report prepared for President George W. Bush included a quote from the Bible. At the time, many of the reports focused on the war in Iraq and the rise of casualties in the region. One of the quotes used was: “Therefore put on the full armor of God, so that when the day of evil comes, you may be able to stand your ground, and after you have done everything, to stand.” The use of a quote such as this infers that there is something very powerful surrounding us, something that we cannot escape. In my work, one effect of the text being visibly skewed is that a viewer cannot stand properly. Here, you are confronted by something that is manipulating you—your body as well as your mind.

DA: The character of Crusoe still shapes the minds of many. The idea of being marooned, alone on an island. What kind of thoughts does it promulgate about civilization at large?

MA: The idea of being isolated on an island has been around for centuries, but it of course has different connotations in different periods. Today, deserted islands are linked with ideas of paradise, of some sort of carefree utopia, whilst in a practical sense it is in fact undeniably unrealistic. The idea of being that isolated actually terrifies most people, including me, but I think people are drawn to fantasizing about being deserted on an island, especially when one is fed up with society in general. The aspect of solitary escape is for instance something the travel industry uses to make us want to go to wherever it is they want us to go. Also, considering rather recent technologies, such as emails, mobile phones, social networking sites and other means of connectivity—of being perpetually contactable—perhaps there is also an increase in the fantasy of opting out, of disappearing to a secluded place, either on vacation (where you won’t really be alone unless you somehow purchased your own island) or forever. And, at the same time, we live in an era in which most places in the world are populated, or at least have been ‘discovered’ and mapped. Our existence is getting smaller, there is nowhere to escape and hide—someone is always emailing or calling you and even if you tried to find somewhere to be alone, others would probably already be there.

DA: What tools and books would you want today if you were marooned?

MA: I wouldn’t want anything, or at least I would like to fool myself into thinking that I wouldn’t want anything.

DA: Tell me about the research you have done into the various linguistic transformations of the Bible.

MA: Line No.1 (Holy Bible) was first realized at Index, The Swedish Contemporary Art Foundation, which is an institution in Stockholm with a relatively small exhibition space. When I was presented with the larger space at Witte de With, I thought it would be an interesting opportunity to incorporate different versions, different translations, different transformations of the Bible. From Aramaic to Hebrew and Greek to Latin to Old English to New English to many different languages of today… The Bible is the most distributed book of all time. In my opinion when you look at it in different versions the content dissolves and what becomes more apparent is the authoritative power of it.

DA: What kind of conversations have you already encountered that have been triggered by your work?

MA: The striking aspect in many conversations I have had with audiences was the sudden reference to personal experiences with the Bible or religion in a broader sense. It was truly interesting to hear how people have themselves encountered this book, and especially the contexts in which they have experienced it. For instance, some people knew the Bible only by way of its ubiquitous presence in Western art-history. This reveals how essential knowledge of the Bible is to the study of the history of Western art.

DA: Why have you embraced the line in your work?

MA: I find the line, by which I mean any line, quite enigmatic. It can be an image portraying something or representing information, whilst still being a line. The length of the line can be infinite, and it can almost be any width. The line also divides and separates—either horizontally or vertically—and, as each side of the line becomes contextualized, it takes on the role of a kind of void space. In the case of Line No.1 (Holy Bible), the line employs a particular aspect, which is due to its nature: it has the distinct psychological effect of coercing whomever is in the room to hold their body at its level, or below it. Wall-based borders such as these are frequently used in interrogation rooms and classrooms. To make people docile, an unassuming line is simply painted on a wall or manifested in another way. I wanted to couple the Bible, as an authoritative text, with such a gesture to explore what effects it might have along with the surrounding geographical territories of the islands Crusoe and Selkirk have lived on.

DA: Do you have any instructions for how the piece should be read?

MA: Not really.

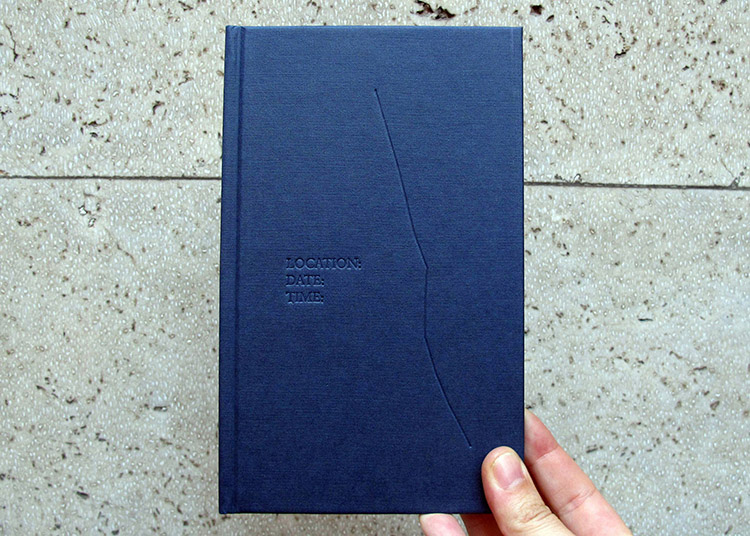

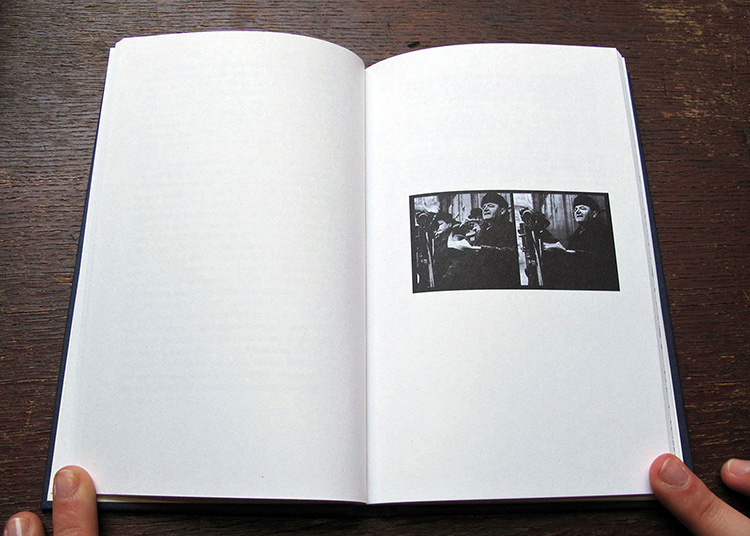

LOCATION:

DATE:

TIME:

2012

Hardbound book

Edition: 500, 72 pages.

ISBN: 978-91-980180-0-4

Photo: Motto

"Written and assembled by Meriç Algün, Location: Date: Time: is both a two-part reflection and demonstration of disappearance in both personal and cultural terms. The first portion contains an essay that illustrates contemporary and historic assumptions of space and time. Rather than trying to articulate the very meaning of lacking substance, Algün writes the idea of disappearance through its converse–documentation, power, place and surveillance. The second portion contains a series of fragments taken from different unnamed sources that both describe and demonstrate erasure in all its moods, ranging from the humorous to the poignant." -Printed Matter.org

Which no one will ever see

2012

Mixed media installation

Photo: Serkan Tunç

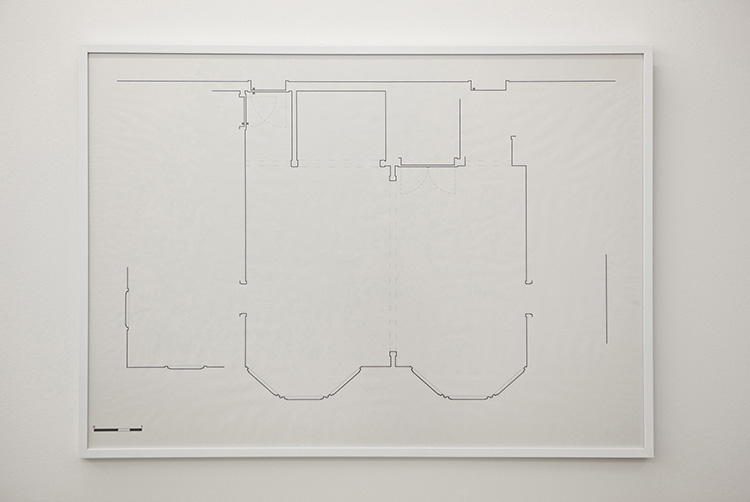

Which no one will ever see is a series of works that originate from the lives of two fictional characters: Harry Caul from Coppola’s film The Conversation and the unnamed protagonist in Antonioni’s Blow-Up and is an attempt to explore issues surrounding the act of surveillance as well the vulnerable relationship between fact and fiction that it entails.

Harry Caul, the protagonist in Coppola’s film The Conversation, is an audio surveillance expert. He is an invader of privacy who can record any conversation between two people anywhere, any time. Caul’s only private pleasure, the one thing that makes him his own person and not those he follows, is playing the saxophone. He is surveillance personified, always listening in on other’s conversations and piecing together the meandering puzzles he overhears but his reasons aren’t personal, he is commissioned to do so. The unnamed character from Blow-Up features another type of shadow figure, the witness. He is a fashion photographer who one day when taking shots in a park accidentally photographs a murder. But we are not sure if it ever happened since when he returns to witness the dead body he saw in his photo, it is no longer there. In the end the truth in the layers and layers of images is turned around and we wonder if the body actually ever existed or if the photo was untrue.

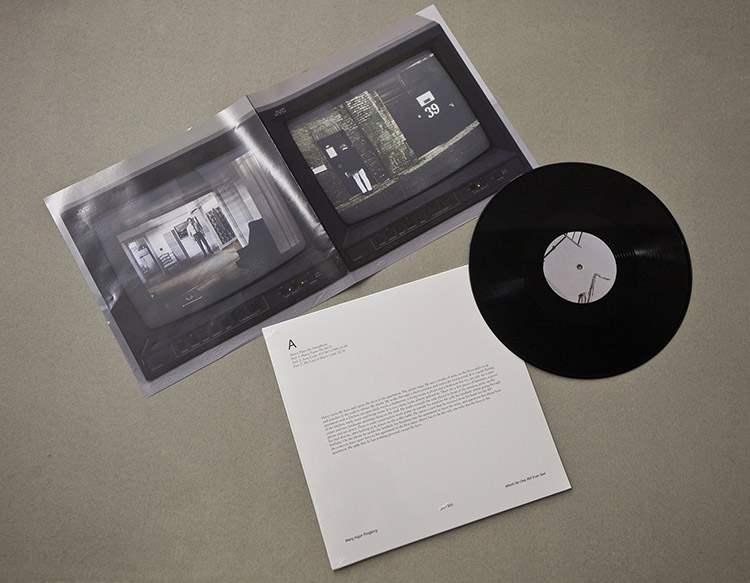

In the works relating to The Conversation one can find Harry plays the saxophone, which consists of the improvised saxophone music played by Caul transcribed and performed. There are three pieces of improvised music and the songs gradually become darker and less consistent, as the character becomes more and more disturbed. Apartment, is the floor plan of where Caul lives conceived by retracing his steps and measuring his rooms in comparison to his body; only drawn from the points where the eye could see. Through this investigation, it became apparent that this character has a symmetrical apartment plan and two entrance doors almost hinting at the double presence he has. Parallel to these, Shadow displays a transparent raincoat hung on the wall, referring to the one Caul is wearing in the film, symbolizing both the visibility and the invisibility of his personality.

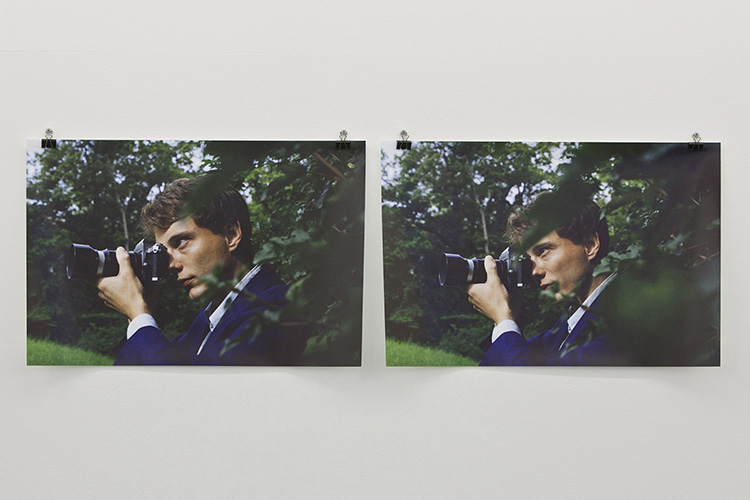

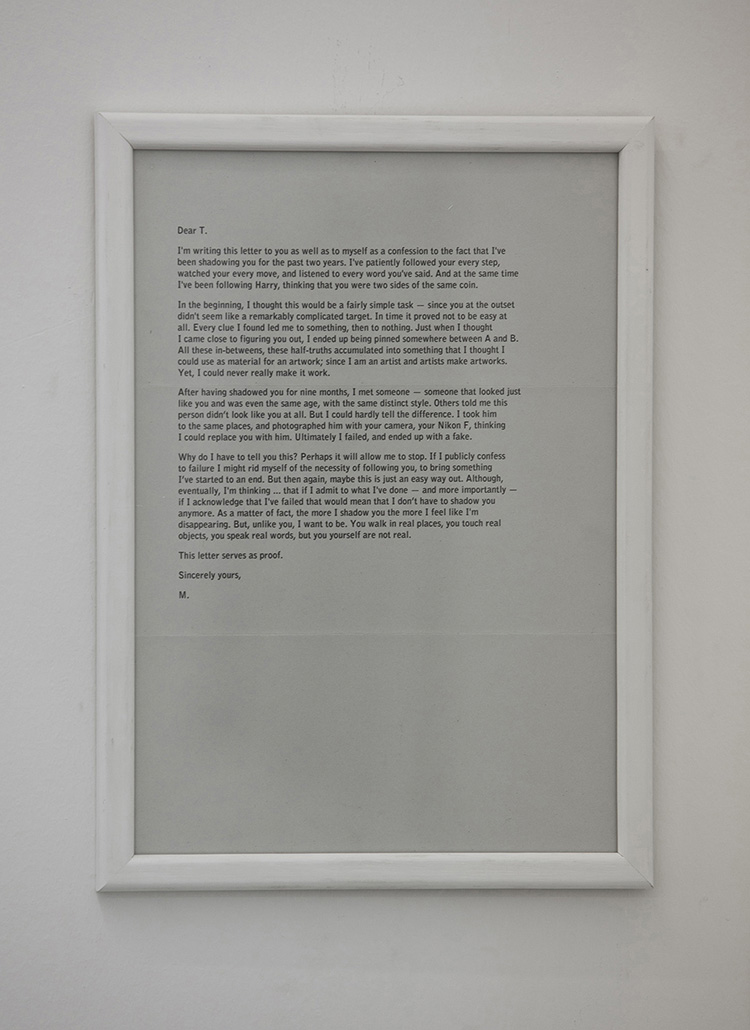

On the other side of the spectrum, I am a photographer is a 13'15" audio recording of what the photographer says throughout the entire film read by a female voice. Taken out of its context and read by the opposite gender, his words twist to the point that his personality becomes more apparent than ever. Bomb, is the photographer's prized object – his Nikon F camera – shown in a paper bag placed in a built-in wall display. The camera becomes almost like evidence from an investigation. Furthermore, Where he was is a map of London, presented in a vitrine under a frosted piece of glass which only makes the parts that the character visits in the film visible. A key point in the entire series is Letter to T. which is a confession letter written to the photographer. The slippery relationship between the factual and the fictional role of this letter enables one to understand that there has been an encounter with a person who looked just like the character and this person was taken to the same places and photographed with his camera as an attempt to replace the main character. Doppelgänger is a diptych of these photographs, where in one of them it is obvious that this person is acting, whilst in the other it is uncertain. The gap between these two poses emphasize the question of reality and authenticity of any type of document that this investigation brings to life.

Time will not record everything

2012

Found and manipulated object, monitor

Dimensions variable

Photo credits: Jean-Baptiste Béranger

The work Time will not record everything is a wall clock with a hidden camera streaming live to a hidden monitor which nobody is allowed to see.

Becoming European

2012

Stamp on drawing paper

3 sheets. 59.4 × 42 cm each

Photo: Åsa Lundén, Moderna Museet, Stockholm

Becoming European displays the dates and ways the artist has resided within the EU and disappeared when beyond their territory, mimicking the manner the Migration Office records her stay. Different colors representing different legal statuses such as blue: tourist, red: temporary resident, purple: pending, black: permanent resident, green: waiting for citizenship, whilst all the absent dates are when she is outside their borders, for instance in her hometown Istanbul. The counting of days ends when she acquired citizenship and the whole period is from 21.Dec.2007 to 03.06.2012.

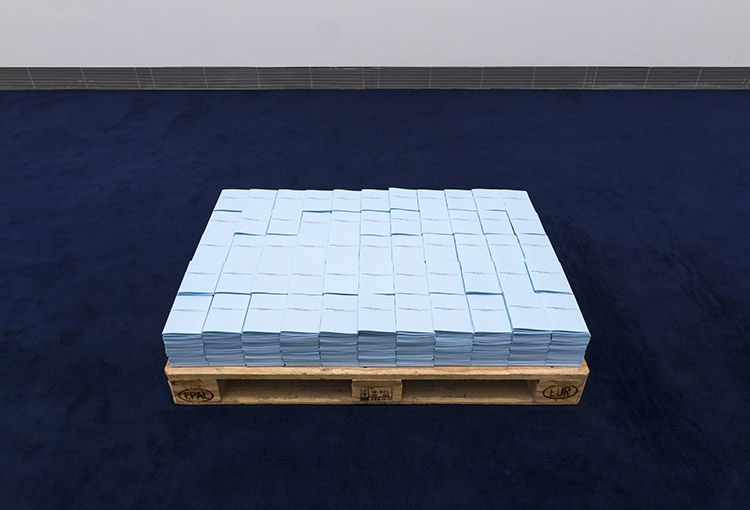

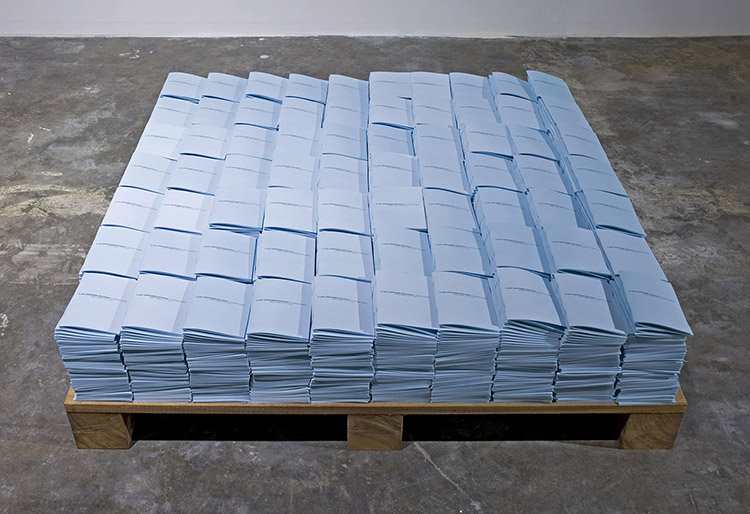

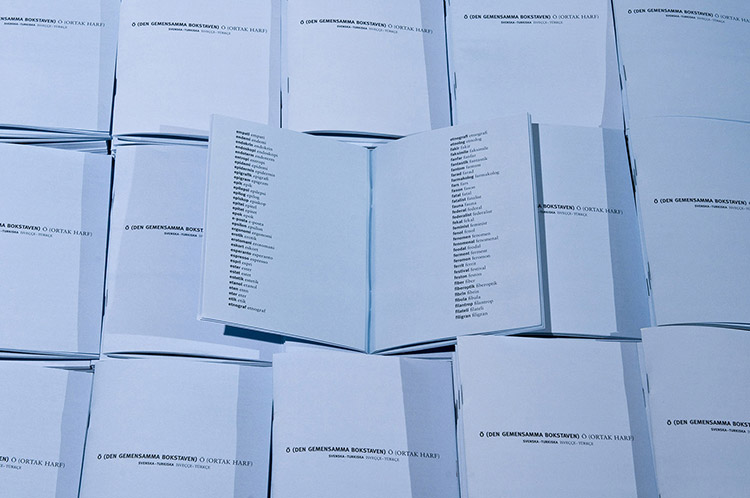

Ö (The Mutual Letter)

2011

Offset print on paper, bound in booklets, EUR-palette, sound

105 x 148 mm, 40 pages, endless copies, palette: 1,200x800x144mm, c.2h, loop

Photo: Nathalie Barki

Click here to listen to an excerpt from Ö (The Mutual Letter)

Interview between Meriç Algün and Adriano Pedrosa, Istanbul Biennial Companion, 2011:

Adriano Pedrosa (AP): Your double presence in the biennial articulates themes of national identity, borders, and translation related to GonzalezTorres’s “Untitled” (Passport), and themes of the double, symmetry, and love, as in his “Untitled” (Ross). Tell me about Ö (The Mutual Letter) (2011). How is the sound installation different from the printed version?

Meriç Algün (MA): Since I moved to Stockholm in 2007, I wanted to collect all the words that are exactly the same in Swedish and Turkish. Only recently was I able to go through the lengthy process of inspecting the two dictionaries, and selecting the words that are spelled and mean the same. In the biennial, my work will be in two parts. The printed pieces take the form of a quite peculiar dictionary, consisting of the 1,270 identical words. Like Gonzalez-Torres’s “Untitled” (Passport), viewers will have the chance to take copies of my dictionary. The second part consists of a two-hour audio recording of all of these words read by my partner and me. Although it might sound like I am unsuccessfully mimicking him, we are in fact speaking our own languages.

AP: Is Gonzalez-Torres an important reference for you?

MA: I have always felt an affinity with Gonzalez-Torres, although I was born nearly two decades after him. If an artist works with these themes, there are often underlying personal reasons and experiences. With Gonzalez-Torres, the nuance is that while it is personal, it is not introverted; it is engaged, and it is there to make a difference. Moreover, he maintains a formal concern and rigor that makes it impossible to perceive his work as accidental. Naturally I enjoy artists who make other types of works, but I must say there are not many artists like him from whom I feel I can draw references.

AP: How are you working through themes of the foreign and the familiar, the personal and the political, home and not-home?

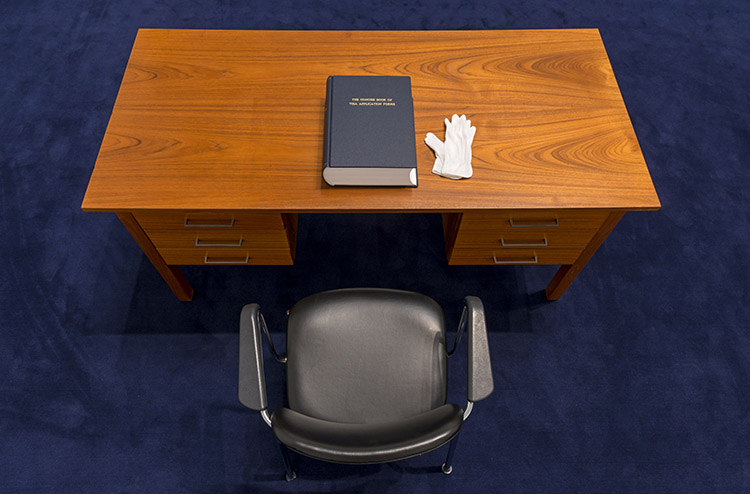

MA: I moved from Istanbul to Stockholm because of love. It is, as with most love stories, far too complex to convey with words and perhaps uninteresting to those not involved. It is enough to say that, as a consequence, I was in a new home instead of my old home. This made cultural identity, language, belonging, and bureaucracy of moving across borders increasingly compelling subjects to me, as I had to apply, wait, be evaluated, and deemed fit to fit into this new society. By appropriating the methodology of collecting, systematizing, and list making, I began working with and against these themes. For instance, The Concise Book of Visa Application Forms (2009–11), which is part of the “Untitled” (Passport) show, is the first work I produced in relation to these themes using this methodology. I was not trying to point a finger at these issues, I was just trying to underline the structures that surround us, to punctuate them and make them visible. I believe I will continue working like this, since unfortunately as subjects they are hard to exhaust.

12th Istanbul Biennial Official Website

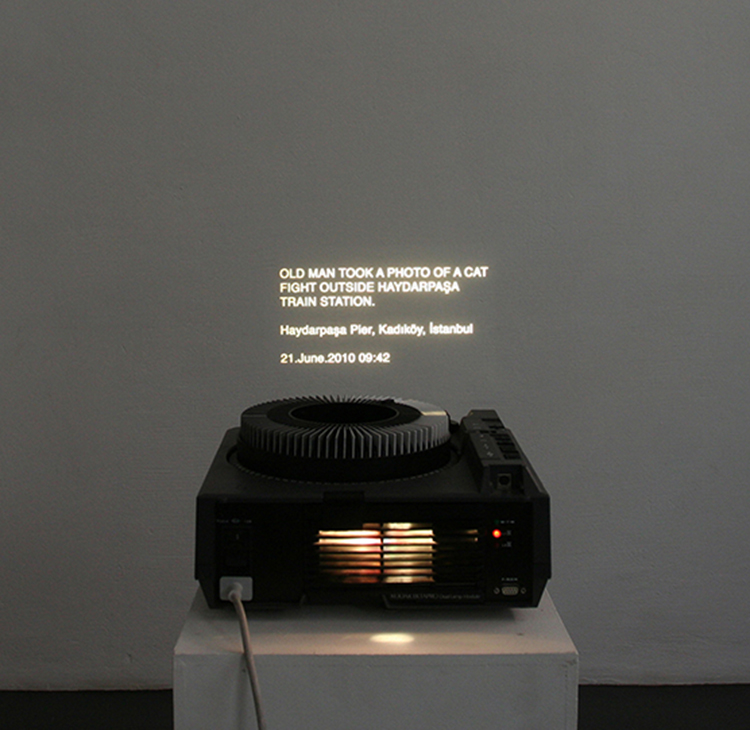

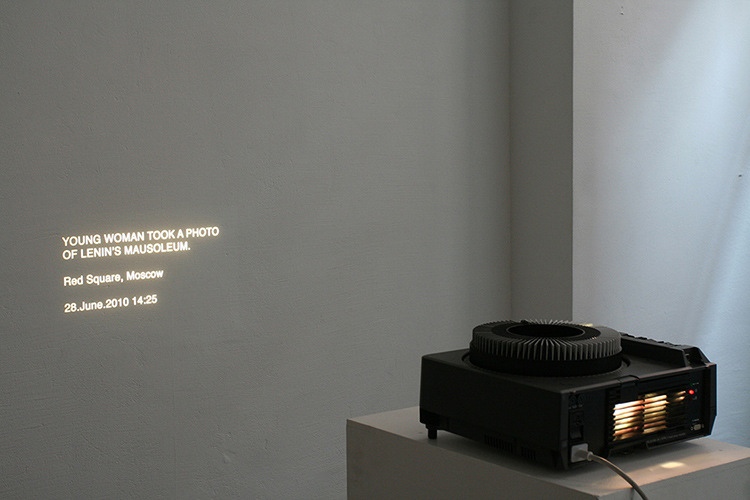

The Risk of Being in Public

2011

Dia projection

136 slides

"The risk of being in public is accidentally appearing on a photograph." -Diane Arbus

The Risk of Being in Public is a yearlong journal containing 136 notations where each account describes a photograph taken in public by an unknown person in which the artist has noticed she appears in the background.

He is really only a white stain

2010

Typewriter on 7 A4 sheets

Taken from Milan Kundera’s novel ‘The Book of Laughter and Forgetting’, the sentence “He is really only a white stain” comes from a story about a man followed by the Stasi and whose life is constantly being recorded. The sentence illustrates the fragility of his existence since, although constantly being archived, he could be erased any moment and become a white stain.

In this work, the sentence is separated into each word and manually typewritten several times until filling an A4 sheet. Using a typewriter creates a visible distance between the self and the action of writing and whilst the action becomes automatic, mistakes occur while writing. These mistakes are later “corrected” with red ink in an attempt to find the true meaning of the sentence, much like the mechanics and aftermath of someone being erased, so to speak “disappeared.”

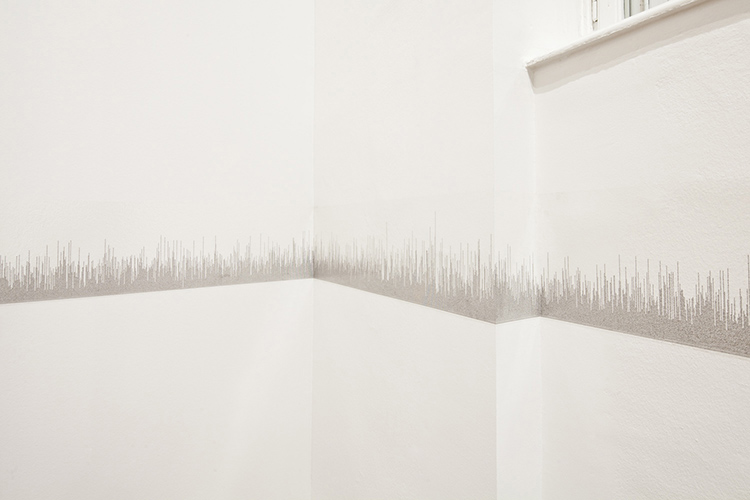

Line No.1 (Holy Bible)

2010

Print on transparent A4 sheets

Dimensions variable

Exhibition view: INDEX, The Swedish Contemporary Art Foundation

Photo: Jean-Baptiste Béranger

In Line No.1 (Holy Bible) two authoritarian components are integrated, a line and the Holy Bible, in an attempt to raise questions on constraints, borders and control. A horizontal line running around a room is said to have the distinct psychological effect of coercing a person to be below or at eye level with it. The line, as an inconspicuous authority traversing the room, is in this instance made up of scripture from the Bible. Permeated in general consciousness, and disregarding specific individual beliefs, the Bible maintains a prominent influence on society at large and is here employed not for its content, but rather for its history as a didactic text. Moreover, the authoritative position of the artist is also acknowledged by further demanding the beholder’s immersion and action through positioning the text skewed and near illegible. In attempting to read, one is inevitably required to adjust body and sight to the form of the work, whilst being influenced by its textual content and commanded by the horizontal line.

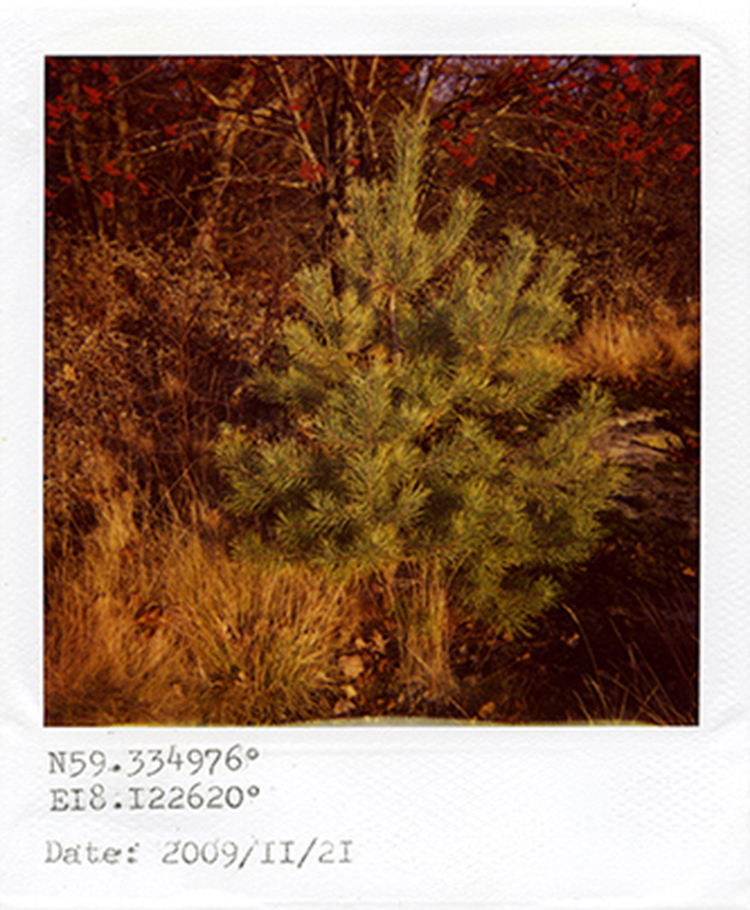

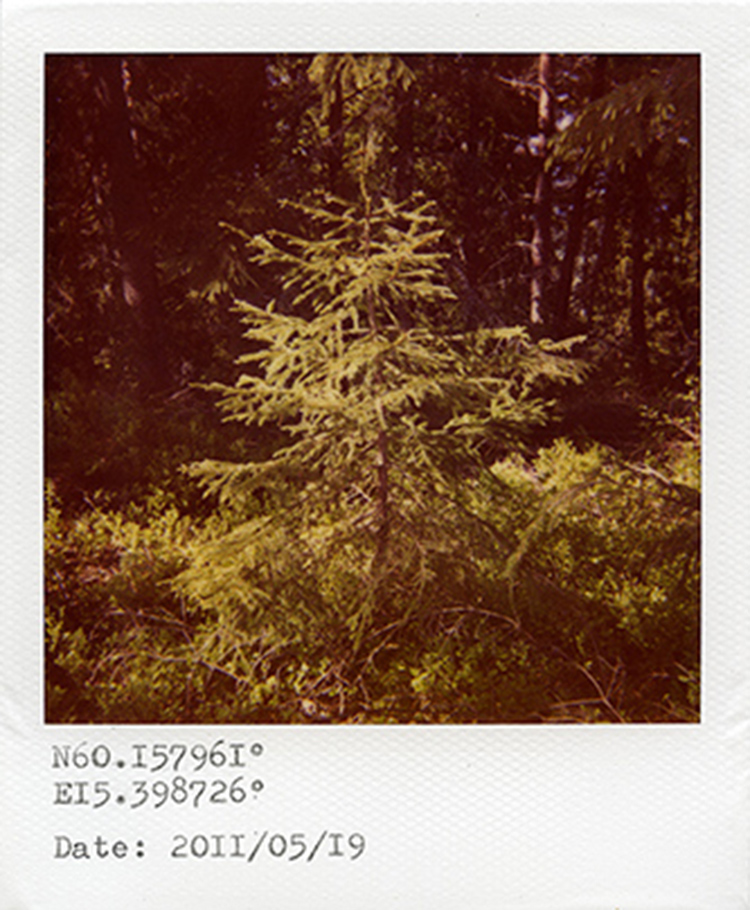

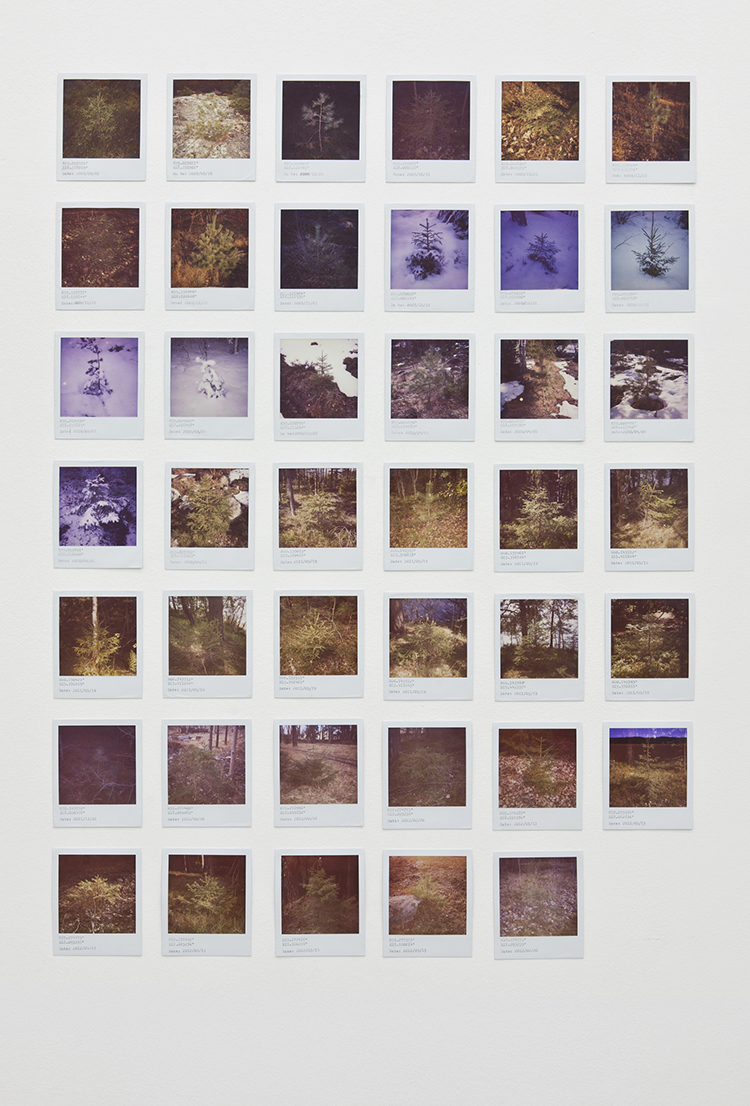

Untitled (Tree Top Project)

2009 – ongoing

polaroid photography

Exhibition view: Francesca Minini, Milan

Photo credits: Agostino Osio

"Meriç Algün is an observer whose works speak to a vigilant and deliberate engagement with the world. Her approach is method-driven. She counts, measures, and weighs; she itemizes, and yet she watches (she may even have watched you). Research is at the core of her artistic practice, yet in her meticulous investigations she does not seek to discover anything new or noteworthy. Rather, she aims to catalog and understand the present, the here and now. In gestures that bring to mind the challenge of trying to isolate the sensation of the soles of one’s feet coming into contact with the ground, Algün seeks to connect directly and viscerally with the world around her. She has expressed this desire by carefully listing the objects in her home, as in Our Home Weighs 1.223.990 grams (2009-10), and by noting every time a stranger snaps a photograph with her in the background, in The Risk of Being in Public (2011).

Untitled (Tree Top Project), begun in 2009, is an ongoing project of observation, documentation, and collection. In a manner reminiscent of Richard Long’s epic walks or Micheal Heizer’s scores into the earth, Algün chronicles her movement through the world. Working in the mode of Bernd and Hilla Becher, who carefully–almost clinically–documented vernacular industrial architecture of the 20th century, Algün uses her Polaroid camera to identify and catalog the tops of a certain type of pine tree, marking each print with the date it was taken, and the latitude and longitude of the point of discovery. Like the Bechers, she is offering a typology without logic: Her photographs do not engage with the scientific, though they allude to its methodologies. Based on happenstance rather than a systematic, research-based agenda, the collection is simply an accumulation of experiences, a visual remembrance of places the artist has been (and the treetops she’s seen)."-Jens Hoffmann.

Text from the catalog Life in your Head. When Attitudes Became Form Become Attitudes: a restoration, a remake, a rejuvenation, a rebellion. Editor: Jens Hoffmann. Published by CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art, San Francisco, 2013.

Our home weighs 1.223.990 grams

2009

UV print on PVC

125 x 250 cm

In an interview with Der Spiegel, Umberto Eco says “We like lists because we don't want to die,” and in his recent book The Infinity of Lists (2009) he further elaborates on the essential nature of lists as being tools to understand the incomprehensibility of the infinite. Such methodology of list making is used in the work Our Home Weighs 1.223.990 grams as a tool to investigate the notion of home. The work is a detailed inventory of all the individual objects in the artist’s home, each item noted with their corresponding weight. Using a scientific measurement unit such as weight extracts the physical reality of the home and makes it factual, thus, more real. Whilst the outcome of the investigation - 1.223.990 grams of belongings in a household of 34 m2 - becomes a point of entry into questions about consumer culture and domestic living, the work also reminds us of the fragility of our own existence and makes the lightness of our being even more unbearable.

Destination: Mali / Peru / Kiribati / India / Brazil

2009-

Found objects

Dimensions variable

Destination: is series of ongoing installations challenging our understanding of what constitutes nations and their borders. The works are centered around transcending the boundaries of countries in an attempt to display the immaterial materials that define the perimeters of specific geographic spaces: its laws.

The works are gatherings of the objects that a traveler, by law, can cross a countries’ borders with. The connecting thread between the objects is the law of a nation and the everyday things on display become representational for that specific geographical space. The laws that direct what can and can not cross borders is a definition of the land itself and the works make these legislations tangible by the displaying of the objects on these lists.

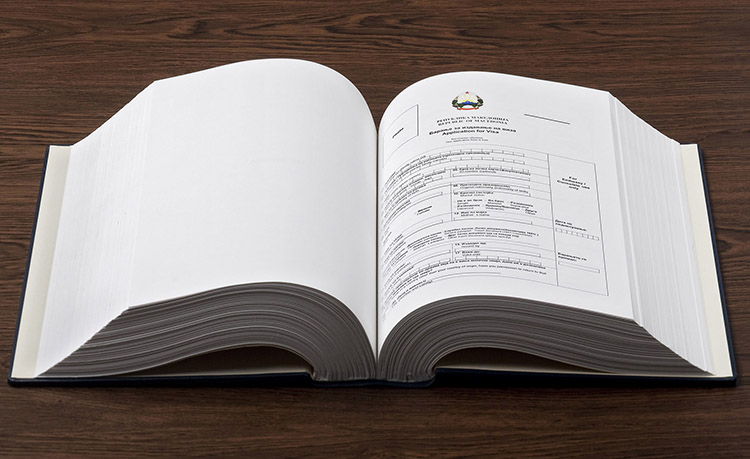

The Concise Book of Visa Application Forms

2009

hardbound book, inkjet print

560 pages, 32.5x24x8.5cm

Photo: Jean-Baptiste Béranger

The Concise Book of Visa Application Forms is a hand-bound encyclopedia-like book consisting of all the visa application forms in the world. In the bureaucratic world of moving across borders, application forms with questions such as “Have you engaged in any other activities that might indicate that you may not be considered a person of good character?” or “Are you and your partner in a genuine and stable relationship?” must be filled and sent to the respective consulates along with a stack of personal documents, bank papers, invitation letters, plane tickets, birth certificates… etc. In this book all of these forms are accessible to the viewer, theoretically enabling him or her to enter a world, which is not as open as we often like to think. The book is an attempt to construct a symbol of a closed world, illustrating also the bureaucracy of moving across borders and what hidden structures traveling and moving depend on.